It seems like the Chinese yuan (also called the renminbi, or RMB) will start gaining value again:

It seems like the Chinese yuan (also called the renminbi, or RMB) will start gaining value again:

The People’s Bank of China said that in response to the global economy’s continuing recovery, it will enhance its exchange rate’s “flexibility,” a statement observers interpreted as meaning that China will let the yuan gradually appreciate against the U.S. dollar. But don’t expect big hikes: “The basis for large-scale appreciation does not exist,” said the bank, which plans to keep its exchange rate “basically stable.”

The move comes one week before President Obama and other world leaders will gather will gather in Toronto for the G20 economic summit, at which China’s currency policy will be in the spotlight.

Chinese officials said the renminbi would move in relation to an unspecified basket of currencies, not just the dollar.

Of course, the Chinese government does not want to give the impression that it cedes to American pressure, which means that the rise won’t be fast (at least in the coming year).

What foreign commentators don’t mention is that many “experts” have recently been invited on domestic TV programs to explain that a revaluation of the RMB was probable this year. The most important issue for Chinese leaders is to avoid large-scale unemployment… Closely followed by persuading their citizens that the revaluation is in the interest of the country (rather than imposed by the US).

What are the short-term effects for importers?

If the RMB goes up (which is probable), prices will mechanically increase. But they should NOT rise as rapidly as the RMB/USD rate, since imports of components into China get less expensive. It is the rare product that is manufactured in China and that does not integrate any imported component or raw material.

It will be more difficult to negotiate long payment terms. For an exporter making 3% net margin, this new monetary policy means high risk. If he is paid 4 months after he buys the materials and starts production, and it the RMB rises by 4% in that time frame, he will work for nothing and lose money on the deal.

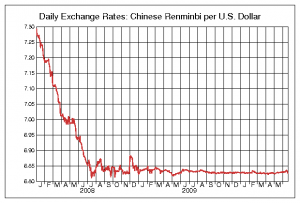

My advice is always “defend yourself with data”. Some exporters will certainly be frightened and ask for 5% or 10% increases, even though it is not even clear the value of the RMB will go up. A good source of information is Pacific Exchange Rate Service. For example, here is a graph of the RMB value against the USD since 1 Jan. 2008:

What are the long-term effects for importers?

First, it is too early to tell before we see what the new policy really looks like. Nobody knows what currencies are in its basket.

Second, I don’t think there will be any significant effects over the next 10 years, except for the most labor-intensive industries (e.g. apparel). And these industries have already started to relocate to other low-cost countries and in the inner provinces. These trends might accelerate.

My bet is that, as Reuters says, China’s new yuan regime looks a lot like the old one.