Most Chinese factory managers have never completed advanced education. But they are generally very savvy at certain aspects of their job.

Most Chinese factory managers have never completed advanced education. But they are generally very savvy at certain aspects of their job.

There is one thing they can’t wrap their head around, though: the fact that the rules of physics and mathematics apply in their factory’s operations.

And that’s a problem. If they accepted that fact, they could accept counter-intuitive conclusions much faster. I am going to walk you though a few such conclusions below, based on Little’s law.

As Pascal Dennis writes, Little’s law in factories is the equivalent of Force = Mass x Acceleration in general physics. Here it is:

Amount of work in process = throughput at the bottleneck x cycle time for production

If we see it from another angle, it is equivalent to:

Cycle time for production = amount of work in process / throughput at the bottleneck

And here are a few of implications:

- There are two ways to reduce the time to produce a certain batch: release a lower quantity of work in process in the system, or increase the capacity of the bottleneck(s).

- If we release more work in process on the factory floor, the cycle time increases. So making a batch of 20,000 pcs instead of 10,000 pcs means the cycle time automatically doubles (all other variables being held constant). (This is rather intuitive.)

We can see this in many situations. For example, when a factory moves to a larger building, it is often surprised that production lead times become much longer.

The reason is, each process has more room for stock and the planners try to take advantage of it by increasing batch sizes (in a misguided effort to reduce average cost per piece). Again, when work in process is higher, cycle time is longer.

Also, buyers should beware of workshops with an ocean of unfinished goods. A factory with large amounts of stock on the shop floor probably needs a long time to ship finished products (much longer than a similar factory with much less stock lying around).

We can also see Little’s law this way:

Throughput at the bottleneck = amount of work in process / cycle time for production

It means that, if there is zero work in process stock in a factory, the throughput is zero. In other terms, production is zero. There is no such thing as a zero-stock factory. The real enemy is excessive inventory.

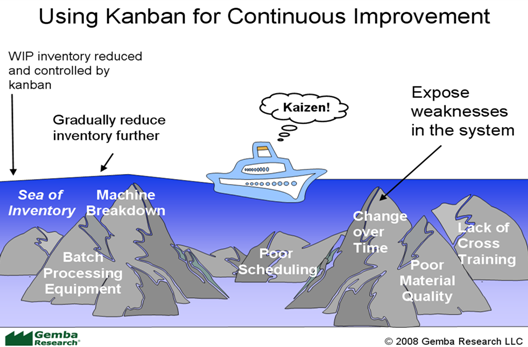

Another reason why too much stock is bad is not linked to Little’s law but it deserves mentioning. Stock hides problems. When a machine is poorly maintained and breaks down, or 100 pieces are found with defects, everybody should try to understand where the problem comes from and fix it. But this is much less of a problem if there is a lot of stock. Production never needs to stop, so the problems are not visible and don’t get fixed.

Lean manufacturers gradually lower the level of inventory to make these problems appear and to address them. This approach is often presented this way (I found this image on the internet, but it’s been drawn in many different ways over the years).

What do you think?

Renaud, I was taught the rocks and lake analogy some years ago, on my journey through learning Lean Manufacturing. As part of TPS, It’s listed as one of the Seven types of waste. The idea being that issues from many departments are being hidden by excess inventory (apart from the money tied up and the lack of Flow), lower the inventory, highlight an issue, attack and resolve the issue. Repeat, long term this = inventory down, costs down, flow up, shorter lead times.

Been following your site form some time now and as a 12 year old China, your posts frequently ring so true to episodes I have myself experienced. Keep up the good work

Peter Gardner

That’s a great explanation, thanks Pete!