A few days I wrote about the trend toward more supplier self-inspections. In certain cases, it makes a lot of sense to stop sending employees to check if a supplier has done a good job.

However, it is not just a case of saying “oh by the way, starting next month we’ll only check 20% of your shipments”, or “good job — we’ll trust you entirely from now on”.

Don’t play Santa Claus. They VERY MUCH want you to stop sending inspectors to their facility, and in exchange you can extract a few concessions… which will reduce your risks further.

But first let’s look at the type of things you want to avoid.

1. Examples of self-inspection reporting gone bad

A few weeks ago, regular reader Brad left these examples in a comment:

1. Measurement correlation. Sometimes the factory and customer measure things using different techniques, different checking tools, etc. Early on this needs to be studied and discrepancies resolved. I am dealing with one of these situations right now where the factory says the products are 100% conforming… but the customer is finding 15% bad. We have done independent checking and have confirmed the customer’s findings. This is an electronic performance test done by a complicated, expensive electrical tester (Fluke brand cable tester, well respected in the industry). Still haven’t figured out what the factory is doing to “pass” the product! We have requested that the factory send detailed test reports, and individual samples; we’ll test on our gear and compare the results on a detailed basis (actual test values, not just pass/fail).

2. Restesting. Suppose there are 10 pieces tested; 9 pass; one fails. The QA person re-tests the failed part and it passes. If testing variation is significant then this could mean that 10% of the shipment is nonconforming, or marginal! Best practice: a formal test procedure that specifies just 1 retest allowed per batch.

3. Sampling integrity. Often when small samples are taken, factory people take the easy way out. Say you can only test 10 pieces per lot. The factory samples 10 pieces. 8 pass. They discard the 2 bad parts and find several more to test, to get 10 passes. They report 10 passes and neglect to report the 2 failures. They rationalize, “only 2 bad pieces”. Truth is that this represents 20% of product!

4. Out and out fraud. I have seen numerous reports where a test report was total fraud. This may be discovered when you ask to see the measurement instrument that was used. Perhaps it didn’t exist! Example: we have a dimension that the factory can only check on a go/no go basis. Yet the test report shows a specific data value. Outright fabrication! Back to Go, no $200!

Brad drove my point perfectly: if you let your supplier do the QC job by themselves, you need to confirm beforehand how they should do it… If you do it later, a few unacceptable batches might already have been paid for and shipped out!

2. Confirming the quality control process

As the examples above suggest, you need to ensure inspections are performed:

- Based on the right checkpoints (nothing missing);

- With the right equipment, properly selected and calibrated;

- Following the right procedure;

- Based on the latest version of the specification documents;

- At the right time during/after production;

- On the right sampling;

- And, when it comes to the search for potential deviations/defects, based on the right standard.

Document all this with as many photos and flow charts as possible.

And make the product scope very clear. A factory might make Christmas trees, but if suddenly they add LED strips to the trees the self-inspection approach no longer works.

3. Evaluating, training, and auditing some certified inspectors

All can be documented, but you need to ensure the right people drive this process. It takes 3 forms:

Evaluating inspectors — they need to have the right psychological traits (systematic, precise…). They shouldn’t be chronic job hopers. They should be able to read and write English if the documents are in English.

Training them — “read these documents and tell us if all is clear” seldom works for operator-style jobs. “let’s sit in a classroom and see how it all works out” also seldom works, especially in China. Learning by doing is the right approach here. And specialized QC software can help standardize reporting and provide statistics automatically.

Auditing them — coming back from time to time to check a batch they just confirmed, and observing how they work, informs the buyer on their reliability and the need for retraining… or for switching to new ones.

4. Regular audits of production systems & processes

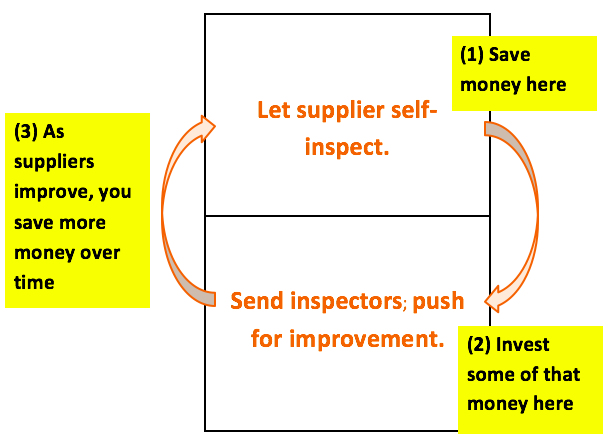

As I wrote in my previous article on this topic, it makes sense to re-invest a part of the savings to drive improvement in your suppliers’ factories.

How to keep pressure on them and show them where the biggest gaps are?

How to keep pressure on them and show them where the biggest gaps are?

By sending auditors there. Sometimes quality auditors who will look at the systems, sometimes more technical auditors who will look at the process controls.

I wrote before about the use of regular audits to drive improvement. It works if you are a large customer of the factories you audit!

—

Related article: Transitioning to Supplier Self Inspections: Go Stage by Stage