I read an interesting book recently: How big things get done, by Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner.

The authors have amassed a large database of “big projects” — from roads and high-speed train lines to airports and nuclear power plants — and have drawn great insights.

I couldn’t help seeing a lot of parallels with the way new products are developed and brought into production. The same typical traps, and the same ‘good practices’ to follow.

But first, here is the introduction to the book, by the publisher:

Nothing is more inspiring than a big vision that becomes a triumphant, new reality. Think of how the Empire State Building went from a sketch to the jewel of New York’s skyline in twenty-one months, or how Apple’s iPod went from a project with a single employee to a product launch in eleven months.

These are wonderful stories. But most of the time big visions turn into nightmares. Remember Boston’s “Big Dig”? Almost every sizeable city in the world has such a fiasco in its backyard. In fact, no less than 92% of megaprojects come in over budget or over schedule, or both. The cost of California’s high-speed rail project soared from $33 billion to $100 billon—and won’t even go where promised. More modest endeavors, whether launching a small business, organizing a conference, or just finishing a work project on time, also commonly fail. Why?

Understanding what distinguishes the triumphs from the failures has been the life’s work of Oxford professor Bent Flyvbjerg, dubbed “the world’s leading megaproject expert.” In How Big Things Get Done, he identifies the errors in judgment and decision-making that lead projects, both big and small, to fail, and the research-based principles that will make you succeed with yours. For example:

• Understand your odds. If you don’t know them, you won’t win.

• Plan slow, act fast. Getting to the action quick feels right. But it’s wrong.

• Think right to left. Start with your goal, then identify the steps to get there.

• Find your Lego. Big is best built from small.

• Be a team maker. You won’t succeed without an “us.”

• Master the unknown unknowns. Most think they can’t, so they fail. Flyvbjerg shows how you can.

• Know that your biggest risk is you.

I’d simply like to cover a few of the interesting insights the authors cover in this book.

At the start, when planning for what to make, don’t hurry. Take time for the discovery stages.

At Pixar, they don’t come up with an idea, draw a few characters and write a script, and then go into production. They are quite careful. They slow things down in the planning (before production) phase. A director can spend years developing a movie.

Exploring ideas and coming up with many iterations comes with a cost, of course. And there is a systematic process of reviews and validations at certain stages of the development. The objectives are as follows:

- Maximise the chance that the movie is a success

- Allow production (where costs are MUCH higher than in development) to go ahead in a smooth and efficient manner

The authors call it “think slow act fast”.

Take a few steps back before diving into technical details

Many organisations have an idea, like it, and quickly get into the details of the design. Then, once there is a detailed design, it looks like it’s been well thought out and is ready to go.

In the context of a new product launch, many companies forget to spend time doing market research, talking to real users and understanding how & why they act the way they do, validating the idea as soon as there is a rough prototype to show, etc. And the result is… many products that are launched don’t meet an interested market willing to buy.

The key is to ask the right questions and have the questions guide the planning phase. What pain does the product solve? Who will use it? How to make sure the product will solve that pain? Will pricing be OK? will the product perform as needed? Will users like it? Will it be sufficiently durable? And so on.

All those questions call for design iterations that can be tested & validated.

The authors call this “think right to left”

Tinker and experiment at the beginning, before getting fixated on one approach

I already covered this in a previous article about proto-testing. Spend some time talking to users and understanding their context. Think of the problem. Think of several approaches that might be a good solution.

Sketch several of them. Maybe you need to buy a competing product and “pretend” it has or doesn’t have certain features, to have an initial mockup of the product you are thinking of. Use that to get user feedback.

There is a lot of talk about using an “MVP” (Minimum Viable Product). In many cases, it should be a ‘Minimum Viable Prototype’ (not a full product), or a ‘Maximum Virtual Product’ (with a nice artist rendering, rather than a physical prototype). The earlier you get market validation, the better.

If you jump onto the first solution you have in mind, you might go for something that is too complicated and for an inferior solution…

Typical project killers

The following elements tend to make any project slower and more expensive than initially estimated:

- Use of a new/unproven technology

- A lot of customisation, rather than going for what people are used to

- One-of-a-kind modules to develop & build, rather than (ideally) the use of standard & modular elements

Design for manufacturing & Assembly

I have written a number of times about DFM/DFMA. See our Youtube video here, and the way we help our clients with DFM here. Developing a new electro-mechanical product from scratch calls for a healthy dose of DFMA work.

The book has a nice story about the way London Heathrow Terminal 5 was built on time and on budget. BAA’s COO was the former head of Jaguar and he knew about DFMA. He applied those principles, with great results.

It is explained nicely on several websites, including that of that subcontractor:

To meet the challenges of this vast project, Arup worked as part of a team assembled by BAA under a bespoke partnering contract, ‘The T5 Agreement’. Co-located, integrated teams involved suppliers from the outset, working together with an emphasis on design for manufacturing and assembly and a focus on safety. Arup provided multidisciplinary services, from project management to people movement studies.

[..] Design management assisted decision-making by consolidating information and presenting it in a clear and consistent way. An example of this success was the 4D planning tool used at the terminal’s interchange plaza. The tool linked CAD data to one or more schedules, helping to identify potential clashes between contractors, and saved £2.5m in the first nine months of use.

All the extra work done in the design stage made the whole project smoother and allowed it to be a success.

How we apply these principles when helping our clients develop new products

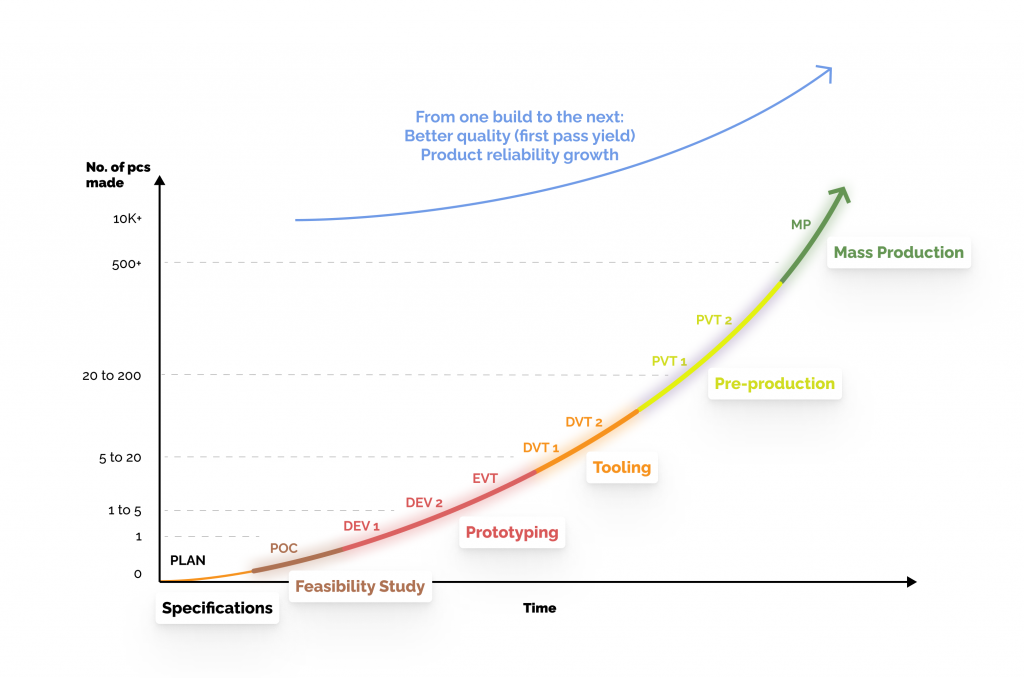

I wrote before about our new product introduction process. And we usually represent it this way.

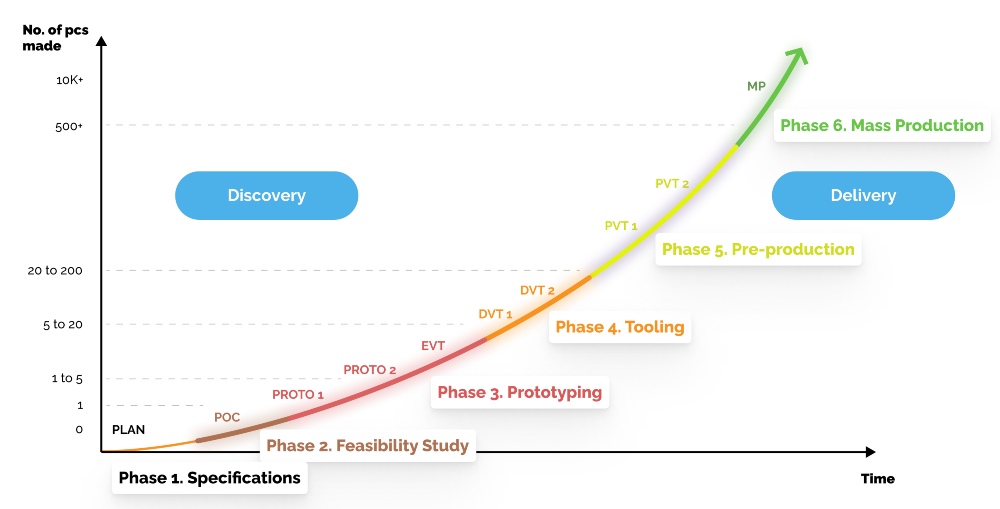

Now, when we explain it to our clients, we usually show it this way:

Things are quite different in the “discovery” phases vs. the “delivery” phases. All the planning work, the early prototypes and the testing & validation need time and attention. Rushing into a final prototype and into tooling is appealing, but it should only be done on mature products that market research has validated.