This article was written by Kevin Howard, a packaging engineer and owner of Packnomics.

A few days ago, we wrote about Design for Distribution. In this article, let’s focus on the design of the components of a product, and the impact it has on shipment from the component suppliers to the assembler.

Design for Distribution should also apply to components that are inbound to the Contract Manufacturer sites. I have worked on many components, where I show the product engineer how to add the ability for a part to be self-stacking, self-nesting, and self-presenting.

I will never be a product engineer designing things that are sophisticated and useful, but none of these folks has ever been taught to think about the cost implications of their designs upon packaging, logistics and material handling.

For complex electro-mechanical products, consisting of hundreds or even thousands of parts, there are far many more packages entering a factory than there are leaving. Here are three common issues:

- If parts are jumbled together in a box, they might cause damage to each other, and certainly make it less efficient for workers to quickly orient the component during assembly.

- If parts are individually wrapped or need partitions, then extra money is being spent on packaging materials and less-than-optimal packaging density.

- If hundreds of parts are in less-than-optimal density, then think of the overall cost impact to a factory site…more pallets, more trucks, more storage space, and more trips to the line to keep it stocked.

How added design function can save on packaging and rework costs

I have worked on both metal and injection molded plastic parts, all with the aim to maximizing inbound component density by replacing packaging material with added design function to each component.

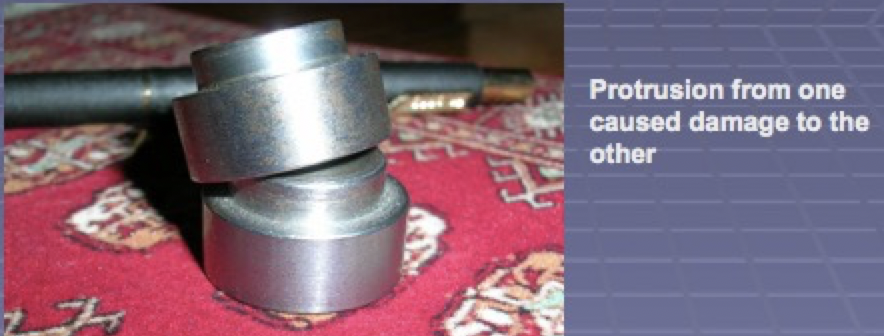

The following example shows a metal bearing.

The company had initially received these simply dumped into a box. Not until after it was installed on the product, would they know that the critical surface was compromised and the product wouldn’t work correctly. These had been press-fit onto a shaft, so it was difficult to then re-work.

They initially wrapped each in PE micro-foam, which is kind of expensive, plus it dramatically reduced the number of bearings/box, thus increasing all the costs associated with poor density.

But they had not counted on what workers would do with this.

The company hadn’t thought about the worker only had the same amount of time for assembly as they did prior to each component being wrapped up. So, in order to keep up, workers dumped the bearings out into a bin from the overwrap whenever they had a few extra seconds. As the naked bearings hit each other, then again damage occurred.

The solution was to get rid of the packaging by modifying the design ever so slightly. The top feature diameter was reduced by 0.4mm.

Now the bearings stood in straight columns, absolutely maximizing box density, fully protecting itself during transport, and keeping all of them oriented the exact same way so as to make assembly more routinized.

I think it’s good practice to ask yourself: how would components and packaging be designed if the assembly station was robotic?

Minimizing packaging is the key, and this is done with extra design effort on the component. I do the same thing when designing foam cushioning, thinking about how to nest the cushions on the inbound portion of their life. Whether it’s product components, overall product industrial design, or packaging, all of them need to take a few extra minutes in thinking about the cost implications over the entire supply chain, from the time they’re made until the time they reach the consumer.

Contract manufacturers or part suppliers often fold in the inbound costs of components to the part cost, thus hiding the inefficiency of their packaging/part designs. Breaking out transportation costs from parts can help lead to breakthroughs in higher efficiency.

Special case: products that are nearly flat

If you think of things that are nearly flat, like metal or injection molded plastic bases of many electronic products, these often have protrusions sticking up to snap together to the case parts or to hold some variety of components.

As a result, these protrusions are like sore thumbs sticking out…they’re both the most exposed features and the most likely to bend or break.

Simply adding other standoff features allow such components to then sit on each other, while automatically protecting the fragile aspects of the design, and doing it all without extra, throw away packaging.

The use of returnable containers

Returnable packaging makes a lot of sense for close-by suppliers. Though the initial cost of returnable bins is much higher than for boxes, they provide much lower overall costs, plus they provide more protection, so they can a great solution.

—

Do you have any questions about this post, or experiences regarding design for distribution and how it affects your business? Let me know by leaving a comment please.

Are you designing, or developing a new product that will be manufactured in China?

Sofeast has created An Importer’s Guide to New Product Manufacturing in China for entrepreneurs, hardware startups, and SMEs which gives you advance warning about the 3 most common pitfalls that can catch you out, and the best practices that the ‘large companies’ follow that YOU can adopt for a successful project.

It includes:

- The 3 deadly mistakes that will hurt your ability to manufacture a new product in China effectively

- Assessing if you’re China-ready

- How to define an informed strategy and a realistic plan

- How to structure your supply chain on a solid foundation

- How to set the right expectations from the start

- How to get the design and engineering right

Just hit the button below to get your copy (please note, this will direct you to my company Sofeast.com):