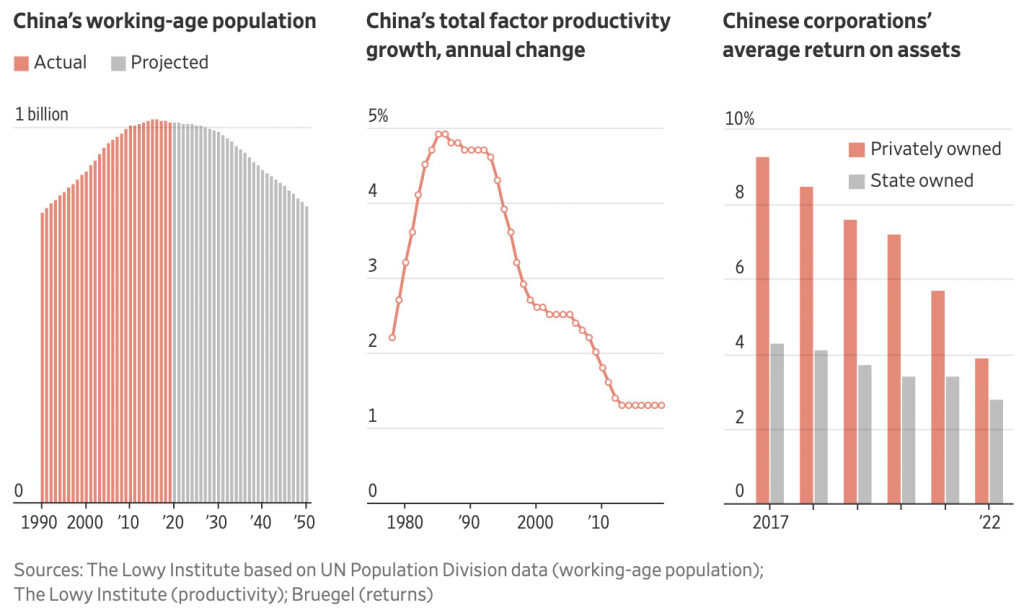

China has had to face a difficult situation recently:

- They have passed their demographic peak and their population is aging.

- A fall in exports and imports is now obvious. The Wall Street Journal just wrote “China’s 40-Year Boom Is Over.“

- A fall in consumer prices (a very worrisome economic symptom) is causing a lot of speculation about an upcoming financial and economic crisis.

- High government debt (probably about 300% of GDP), coupled with slower growth and falling real estate prices, which means it probably can’t spend its way out of the crisis like it did in 2009.

- A new ban from the Biden Administration, basically preventing US companies from investing in most of the Chinese high-tech sector.

As always, a few graphs (from the above-mentioned WSJ article) can do a great job at explaining the situation:

And a lot of people are wondering where all this is going to lead the World’s second richest country.

Let’s first look at the export trends in order to understand what is happening in international trade, and then let’s think of how this may impact importers.

The USA’s desire to gradually ‘decouple’ seems to be working

In How U.S. and China Are Breaking Up, in Charts, the Wall Street Journal shares this impressive graph:

The Washington Post looks at the numbers from another angle:

Chinese products account for roughly one out of every six dollars Americans spend on imports, down from nearly one in four before the pandemic, according to Oxford data. Japan also is buying less from China.

China’s growth has been driven in good part by exports, and cutting the large & lucrative USA market obviously doesn’t help.

But it’s more than the USA market. Let’s say a company develops a certain product and intends to sell it to the USA, Canada, UK, Australia, and continental Europe. Making it in Vietnam or in Mexico helps a lot for making money on the USA market, so manufacturing moves to a new country. In other words, the manufacturing for selling into all those countries exits China at the same time…

It’s been hard, or near impossible, for many SMEs to move production out of China. True. However, large companies have it easier. And they move enormous quantities of products. Give it a 4 or 5 years (since Trump’s tariffs), and it can dig a big hole in trade statistics…

Wait, the statistics may be lying…

Trade statistics only account for the place of final assembly of finished products.

When a Chinese manufacturer of screwdrivers opens a Vietnam factory, sends made-in-China components, does only final assembly there, and ships officially “made in Vietnam” products to the USA, it counts as Vietnam exports. Even though 80% of the value added might come from China.

When a Bangladesh agent buys fabric & accessories in China and arrange for cut & sew in Dhaka, same thing.

So, I think the fall of exports from China to the USA or to Japan is a bit over-blown, as I am writing this.

… but deep changes are under way, no doubt

There is an important phenomenon to keep in mind.

As the Financial Times reported in iPhone maker Foxconn’s cautious pivot to India shows limits of ‘China plus one’:

“Currently we are only doing assembly, but everyone hopes that we can make components and modules, such as casings and screens,” said one [Foxconn] executive.

People familiar with the company’s plans said these steps would be largely limited to Foxconn group companies for the time being because a large portion of the China-based supply chain consists of Chinese producers, which are having difficulty getting allowed into India.

What is going on here?

When big electronic companies move final assembly to Vietnam or India and force their key suppliers (of displays, batteries, motors…) to also move there, it takes them a while to grow their facilities there to meet demand. Right now, they are only producing for that big electronic buyer. That’s, for example, Foxconn trying to ramp up their India operations for Apple. (Foxconn also makes a wide range of parts, they don’t just do assembly.)

The local supply chain is also stretched. Let’s say a decision is made to buy the casings from domestic suppliers. These suppliers are going to be challenged and overwhelmed for some time.

In a few years, though, the situation will be different. These component manufacturers that relocated there will start to accept orders from midsize customers, and that will make a big difference for SMEs. The local suppliers will have learned how to manufacture consistently with low tolerances, and how to work with various types of customers.

All this creates the conditions for moving more and more productions to Vietnam, India, Mexico, and maybe also places like Malaysia, Turkey, and others.

Remember, 25 years ago, companies used to ship components from Taiwan, Malaysia, the USA, etc. into China. Over time, the situation reversed and China now has an amazingly deep and diverse supply chain. The situation can change again.

On the positive side, foreign buyers can capture opportunities

Chinese manufacturers are looking for more business. Their pricing and their terms tend to be more flexible. The RMB is rather low, at 7.25 to 1 USD. Some smart buyers are signing good deals.

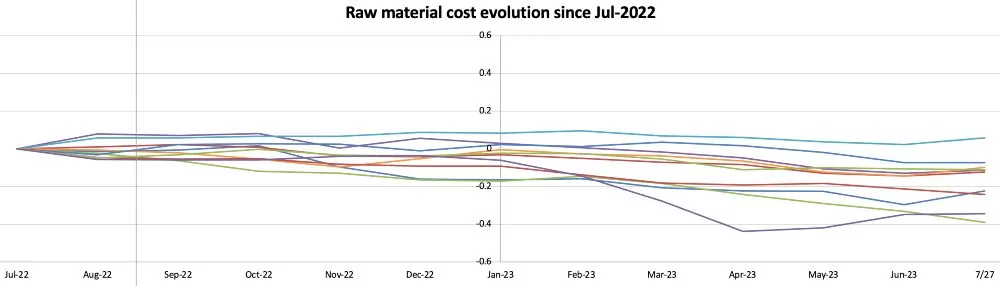

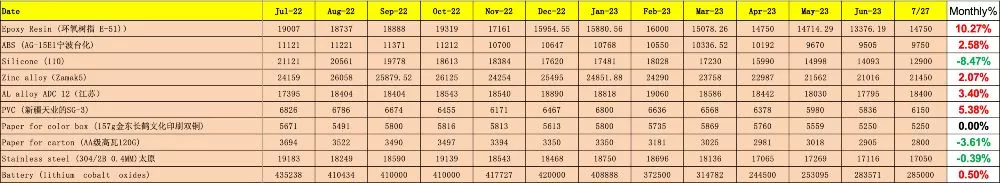

Raw material prices in China have also tended to go down recently, as we reported 3 weeks ago:

And ramping a manufacturing operation up is easier:

- Many factory owners are more likely to entertain the idea of selling their companies or key pieces of equipment. Finding good CNC machines, injection presses, etc. is not difficult.

- Good technical talent is easier to find than, say, in 2017.

Now, be careful — it also means there are more scams. Lawyers see a big uptick in scams.

Many factories are desperate. They are near bankruptcy. The owners owe money to various parties who are not always accommodating. Taking shortcuts is tempting. They don’t worry much about their reputation on the market…

For buyers, the fundamentals are still the same

Certain things don’t change:

- You need to vet potential suppliers.

- You need to set clear requirements for your manufacturers and get their written confirmation.

- You need to check the quality of your productions.

- You need to regular face to face meetings if possible. You need to force structured communication.

- Beyond a certain point, you should not push any further to enlarge your margin.

Don’t rush. By deliberate and systematic. Your processes should protect your interests, don’t skip them.

What if the situation gets really bad?

That’s the question that keeps a lot of people up at night.

I won’t pretend to write intelligently about geopolitic tensions, political agendas, military strategies, and similar topics. So, let’s look at the situation in a simple way.

If the economic situation goes bad, especially with high debt levels, China may not be able to re-invest massively. It will most likely depreciate its currency and do all it can to boost exports — its historical growth driver. That might be good for exporters, until the USA and other countries set trade barriers to counter those excessive incitations to export.

If the situation goes bad for an extended period of time, China may suffer a “1990s Japan” syndrome. Prices may go down for a while. Not bad for importers in the short term.

In both cases, I can’t imagine Chinese entrepreneurs stopping their conquest of world markets. They will keep fighting. And lower demand in their country may increase their appetite for grabbing market share abroad. Which brings me to the next point…

If Chinese companies get too aggressive on their worldwide markets, there may be a serious pushback from some other countries. That’s what the authors of the book Enterprise China have predicted (I interviewed them a few months ago and they make some great points).

This scenario may play out first with electric vehicles sold on the European market. BYD recently called for putting down old legends in its industry. Wow. They may just be getting started.

Now, if the temperature goes up a few notches on the military front, the consequences are quite different. A much stronger ‘containment’ strategy is likely to be applied. Products sold in North America, Australia, and Europe will have to find other sources, at an accelerated pace… That’s really, really, not good for trade.

—

What other likely scenario(s) do you see? Am I forgetting something important here, in my analysis?