A lot of quality/reliability issues are the result of a poor engineering change notification & approval process or the complete lack of such a process. That’s especially common in the context of OEM/ODM manufacturing.

Let’s uncover why…

The first step: the Engineering Change Request (ECR)

Let’s say the buyer wants a change made to a material, a drawing, or a process. They will tell the manufacturer. It may be quite unspecific, and at that stage that’s fine. That’s the start of the ECR (or ECO — Engineering Change Order — as many companies call it).

Sometimes the change needed is obvious: “we might get a short circuit here because all these cables are tightly packed together and it’s dangerous because it includes high-voltage cables” — the easy answer would be “let’s add isolation”.

Sometimes the request only shows a general issue (“find a way to make the bike sturdier”) and it could be approached in several ways. It’s important first to clarify what is needed and to make sure everybody understands the level of improvement requested.

In all cases, a process has to be followed (see below, in the paragraph about ECA). If a countermeasure is implemented right away without much thinking, it may lead to unintended consequences.

The (very common) lack of Engineering Change Notifications (ECN)

Here is a very common issue. The manufacturer decides to make a change unilaterally, for example, to make a corner a little rounder so it can be cut more easily, or they change to a new plating supplier that is cheaper and easier to work with, or they use a different capacitor because the one they usually buy is out of stock. And they don’t tell their customer. There is no ECN (engineering change notification).

In China, that’s so common, that professional buyers have come to expect it. Lawyers who draft development and manufacturing agreements always tend to include a duty to notify the customer of such changes.

However, for some reason, in certain countries, the OEM or ODM feels they “own” the product and owe no flow of information to their customers. Transparency is not to be taken for granted!

Oh, and in regulated industries, a certifying body and/or a governmental agency also needs to be issued with an engineering change notification in most cases.

What is the Engineering Change Approval (ECA) process?

Notifying related parties of the change with the engineering change notification is one thing. Getting approval to carry on with the planned change is another one. It usually unfolds this way:

- The person who suggests the change should get it specified, so it’s clear what the ‘before and after’ look like. It is also essential to explain the context and the “why” behind the request.

- A process of internal reviews, typically from engineering, quality, purchasing, and production, take place. They may raise some issues or point to certain risks. For example, quality people may look at the process FMEA and update it with new information. If necessary, some validation tests are carried out.

- The customer and other outside interested parties need to be notified and need to approve the change. Again, if necessary, some validation tests are carried out.

- The change is implemented if all the lights are green. The relevant documents (SOPs, WIs, control plans, etc.) are updated, people are trained, etc.

(This is a simplified view of the process, and different companies need to do it in different ways in their different contexts.)

Note, that this may be done from one prototype to the next during the development of a new product, or from one production batch to the next.

What do quality management system (QMS) standards require?

The most common QMS standard, ISO 9001:2015, requires the following:

The organization shall identify, review and control changes made during, or subsequent to, the design and development of products and services, to the extent necessary to ensure that there is no adverse impact on conformity to requirements.

The organization shall retain documented information on:

- design and development changes;

- the results of reviews;

- the authorization of the changes;

- the actions taken to prevent adverse impacts.

If a company has followed the 4-step process I outlined above, they are pretty close to fulfilling these requirements.

The ISO 13485:2016 standard, which applies to medical devices, adds a few requirements, such as:

- Verification of the change (typically by making samples under the new design and verifying their performance);

- If appropriate also a validation of the change (sometimes involving a new clinical trial);

- And a much more thorough evaluation of the potential effects of the change.

But this is all getting a bit too theoretical. Let’s look at 2 well-known and well-documented examples, from publicly known sources.

Examples of engineering changes that were not validated the right way and led to catastophic failures

Let’s look at how engineering change orders caused 2 airplane crashes.

1. Atlantic Southeast Airlines Flight 2311

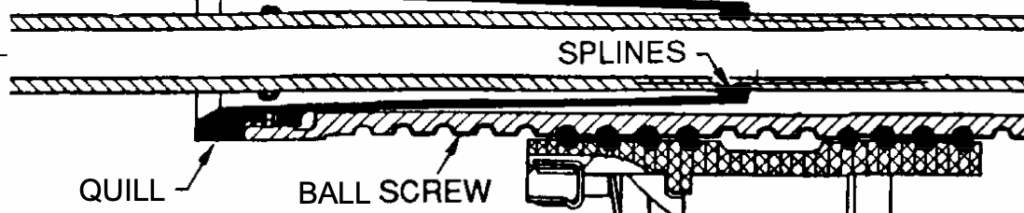

A flight crashed because of an engineering change — change made to splines, which became much harder, to the point where the quill teeth got worn down quickly.

Here are details from the accident report:

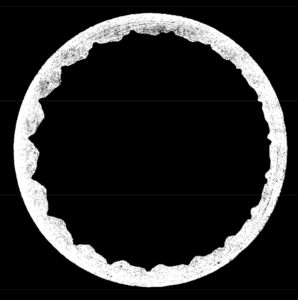

The discrepancy in the propeller control unit was found to have been extreme wear on the propeller control unit quill spline teeth which normally engaged the titanium-nitrided splines of the propeller transfer tube. It was found that the titanium-nitrided surface was much harder and rougher than the nitrided surface of the quill. Therefore, the transfer tube splines acted like a file and caused abnormal wear of the gear teeth on the quill. The investigation found that wear of the quill was not considered during the certification of the propeller system.

Here are the worn teeth of the quill:

What should have been done? As part of the engineering change process, Boeing should have validated that, over the lifetime of those parts, they would interact together as expected. Some reliability testing (life test) may well have led to discovering this issue.

2. China Airlines Flight 120

This plane got engulfed in fire after landing in Okinawa (see video of the fire here). Why?

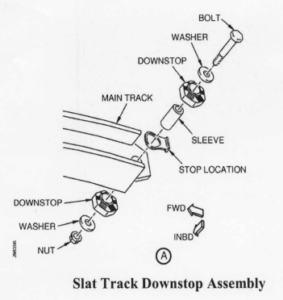

Boeing had ordered a work order on all 737 planes to ensure a piece of the airplane (a downstop assembly) was less likely to puncture the fuel tank.

The change was tricky for the maintenance technicians, who have to work with their hands up, inside a wing. They needed to feel the parts with their hands and couldn’t really be sure they did a good job. In some cases, they didn’t notice the washer fell down.

And the missing washer meant the downstop part was no longer filling its role… and became even more likely to puncture the tank — the exact opposite of what this work order was aiming at!

As part of the engineering change process, Boeing should have validated that the work could be done consistently well and that the maintenance technicians could confirm it had been done well.

In the US alone, when that part was re-checked, many instances of a missing washer were found, and they had to be reworked. So, that work order might have caused several other planes to get on fire.

****

How about you? Have you documented a process that every engineering change request needs to go through, as it gets approved or rejected? Many companies put together a simple form for that, and add to it over time based on their experiences.

And how tightly do you work with your suppliers and customers? Do you see many engineering change notifications of ECRs/ECOs? Is it working well?