Some buyers don’t want random inspections. They don’t trust the manufacturer to produce consistently at the right quality level. So they need to check 100% of the goods.

Some buyers don’t want random inspections. They don’t trust the manufacturer to produce consistently at the right quality level. So they need to check 100% of the goods.

A few months ago, I described inspections on a platform, where the shipment is inspected outside of the factory before being shipped out (if it is accepted for shipment). Some large importers of apparel resort to this solution. It is also very popular with Japanese buyers.

However, it is impossible in countries like Indonesia, where most factories are in free-trade zones (and are considered bonded warehouses). The manufacturers get the fabrics and the accessories free of import duties, and they must ship the goods out directly. They can’t take the products to another warehouse.

Then, how do demanding importers do, when platform inspections are not an option?

The line inspection process

I recently met with the founder of Saxa, an Indonesian quality control firm. He explained to me that they set a team of 10 ladies at the end of each production line.

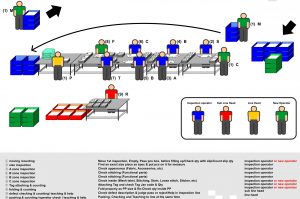

I got the below explanation from Saxa’s website (click on the image to enlarge).

The process looks like this:

- The QC team checks the garments and sorts out the defectives

- The factory packs them

- A QC team member checks the quantity and breakdown inside the cartons, which are then sealed.

There is one problem with this setup: the manufacturer doesn’t care about the 15% of pieces that need some rework. They are not aware of what it costs them, therefore they don’t make efforts to improve their reliability.

How to align the buyer’s and the manufacturer’s interests?

Saxa recently started to adopt a different approach with the help of some clients:

- They start with piece-by-piece inspection (paid by the manufacturer)

- They see what defects come up most often

- They give advice to the manufacturer to decrease the most frequent defects

- If the proportion of defectives goes below a certain target, they switch to random inspections (paid by the importer)

- If the proportion of defectives goes back up, they switch back to piece-by-piece inspection (paid by the manufacturer)

I love this deal. In the mid-to-long run, it decreases the costs for the importer by forcing the factory to address the real issues.

What do you think? Any similar example?

Yes, that is a good idea, but not easy to setup following the product. When we redact the contract for the buyer, we add some clause for the delivery of spare and to manage the return in warranty by cheap transportation. The factory and supplier found advantage to have spare directly near the final customer.

Well, of course it is a huge advantage if the customer can have extra spare parts and can return products under warranty. But you need a good contract, and solid suppliers for that!

I first became involved in QA in the US Auto industry in 1985. At that time it became clear that we were losing the quality competition with the Japanese, particularly Toyota.

The big manufacturers (GM, Ford, Chrysler) had been doing advanced QA for some years but it clearly hadn’t been working well enough. Around this time, we began to shift from an inspection mindset to instead use process control, process capability measurement, and remediating inspection. This required a big change in thinking. For complex products like cars, airplanes, or computers, any measurable level of defects is troublesome. Work the math. Assuming a 99.9% reliability rate, and the chance that any single failed part can cause a defect in the assembly:

If the product has 1,000 parts, the probability of a defect in the assembly is 64%

If 5,000 parts, probability of a defective assembly is 99.4%

10,000 parts, probability is 99.996% — in other words, it is all but certain that the assembly will have a defect.

I am not expert in the airplane industry but I believe that some large airplanes have over 1,000,000 parts.

If there are multiple units of the troublesome part in the assembly (say, 4 tires or 6 spark plugs), the situation gets worse yet. (It’s also true that with good design. Engineers improve reliability by creating redundant, parallel systems so that if one piece fails, another can take the load.)

Of course, if you are making simple products like socks or shoes, deaths due to defects are unlikely. But defects in cars can kill people, including innocent bystanders. As an auto quality guy I take this personally.

Instead of building a batch, doing sample inspection, and accepting or rejecting, the new approach was:

Determine the process capability (statistically).

If the process showed good capability, pack the goods and do a sampling inspection as an audit. If any defects were found, sort the batch 100%.

If the process could not prove capability, inspect 100% at the process.

In later years this was refined to include further inspection stages.

If the customer found any defectives at their location, alert the supplier and ask for immediate 100% inspection and a resolution of the root cause. Once the root cause was corrected and capability restored, the 100% inspection could be removed.

If the customer experienced repeat problems after the supplier claimed a successful resolution, a 100% redundant inspection was to start, with inspection method defined by the carmaker. GM, for example, called this Level I Containment.

If the supplier’s containment still allowed repeat problems to slip through, then the supplier is mandated to hire a GM-approved third party inspector to do this checking, at the supplier’s expense (Level II Containment). The third party reported to the supplier as well as to GM.

Level II inspection continued until the supplier demonstrated the details of their process correction to the third party inspector, and completed 30 days of defect free checks.

In addition to bearing the expense of the additional inspection, the supplier would usually get a management visit from the OEM’s purchasing people. You can be sure that offering the supplier more business wasn’t on the agenda.

A separate strategy was to incorporate automated 100% checks for critical parts. Many brake parts, for example, get an automated 100% check as part of the production process. Similar expectations exist in electronics.

So, yes, there is a definite place for 100% inspection by third parties.

Thanks a lot for your extremely interesting comment, Brad! I love it.