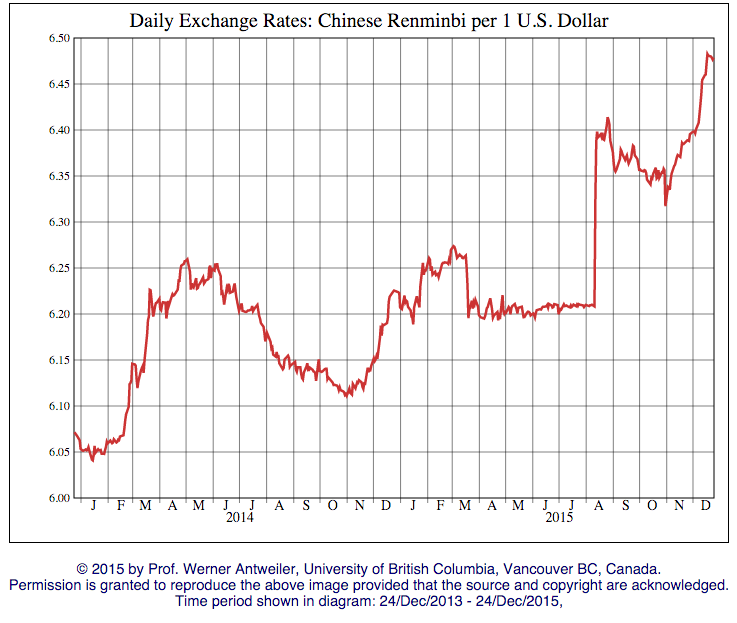

Good news for importers: you can buy more and more RMB with 1 USD.

Good news for importers: you can buy more and more RMB with 1 USD.

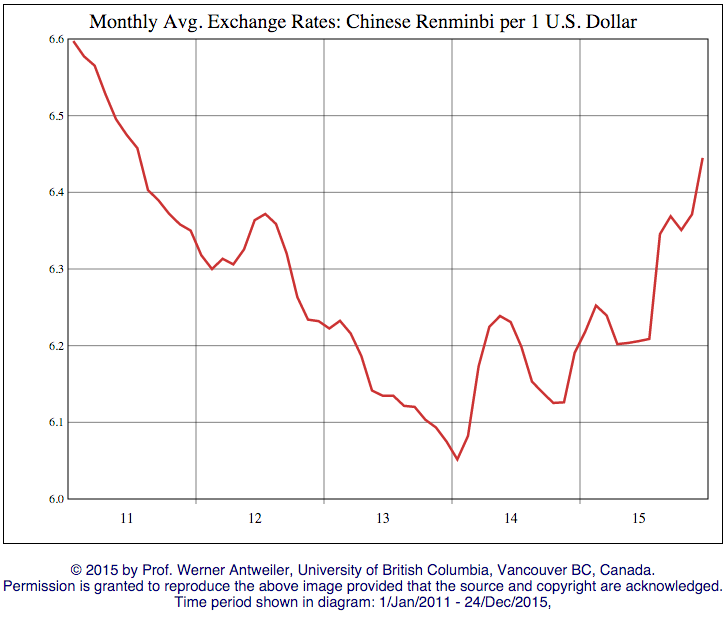

To put things in perspective, we are now back to the level of mid-2011.

What happened recently?

I certainly don’t pretend to have the full picture. Many things happen behind the scenes. But I can see three things at work:

- The Chinese economic growth is slowing down, while domestic consumption is still weaker than Beijing would hope. It means they need to stimulate exports.

- Inflation in China is not a big problem right now. I remember in 2008 when everybody was complaining about the price of pork meat (which had doubled in one year) — there is no such problem at this moment.

- China has gained a symbolic battle when the IMF agreed to include the RMB in its basket of reserve currencies. As explained in this article by The Economist, it will favor a weaker RMB:

The reason is that the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) will now find itself under more pressure to manage the yuan as central banks in most rich economies do their currencies—by letting market forces determine their value. In bringing the yuan into the SDR, the IMF had to determine that it is “freely usable”. Before coming to this decision, the IMF asked China to make changes to its currency regime.

Most importantly, China has now tied the yuan’s exchange rate at the start of daily trading to the previous day’s close; in the past the starting quote was in effect set at the whim of the PBOC, often creating a big gap with the value at which it last traded. It was the elimination of this gap that lay behind the yuan’s 2% devaluation in August, a move that rattled global markets. Though the yuan is still far from being a free-floating currency—the central bank has intervened since August to prop it up—the cost of such intervention is now higher. The PBOC must spend real money during the trading day to guide the yuan to its desired level.

Inclusion in the SDR will only deepen the expectations that China will let market forces decide the yuan’s exchange rate. The point of the SDR is to weave disparate currencies together into a single, diversified unit; some have suggested, for example, that commodities be quoted in SDRs to reduce the volatility of pricing them in dollars. But if China maintains its de facto peg to the dollar, the result of adding the yuan to the SDR will be to boost the dollar’s weight in the basket, defeating the point.

What would happen if China really did give the market the last word on the yuan? For some time it has been under downward pressure. The simplest yardstick is the decline in China’s foreign-exchange reserves, from a peak of nearly $4 trillion last year to just over $3.5 trillion now—a reflection, in part, of the PBOC’s selling of dollars to support the yuan. Were it not for tighter capital controls since the summer, outflows might have been even bigger.

How high will it go? 6.8 RMB for 1 USD? 7.0? Higher?

How to take full advantage of this trend? You can get quotes in RMB and settle what you purchase in RMB, as I explained here. A number of large companies are already doing this, and there is no reason midsize importers can’t do this.

Hello,

Thanks so much for your article, i will bring an oher analysis from experience, buying from many year in both RMB/USD choosing for each order.

This situation allow chinese company to keep margin with fix sale price in USD even if theyr net price increase in RMB due to inflation.

When you negotiate in RMB, you need to face to very high pressure by the supplier to increase the sales prices in RMB.