By now, companies that rely on China to supply some products or parts have generally grasped the current situation with the COVID-19 epidemic that is leading them to wonder if it’s important to diversify manufacturing sources away from China alone:

- A large portion of the Chinese population is forced to stay home (up to 760 million, according to the NYT)

- In many areas, local authorities have taken the matter in their hands and nobody knows when they will change policy

- It means manufacturing organizations have insufficient human resources and are unable to function in normal conditions even after they get the local government’s approval to open

- There is a change this scarcity of labor pushes wages up quite a bit (this is not clearly the case yet, but I wouldn’t rule it out).

- No one knows when the situation will get back to normal. March? May? August? Later? The uncertainty itself is a killer…

- The economic impact might be enormous, and many factories might go out of business.

At the moment, the highest losses are in the auto industry, where massive assembly plants are shut down for lack of component(s). I mentioned the reasons behind this in my last article: many components; just-in-time inventory management coupled with long supply chains; single-sourcing.

And many importers are very worried. If continuity of supply is interrupted, an entire business is suddenly on a straight road to bankruptcy.

Will such a supply crisis happen again in the future?

The factors that led to an epidemic are getting stronger with time (high population density in cities, fast transportation modes, etc.).

And, when the same disaster strikes twice in the same country, it doesn’t mean that the country is better prepared the second time. After SARS in 2003, did China keep an adequate ‘strategic reserve’ of facial masks? Did they set up a central commission that doctors have to call immediately for any suspicion of a potential outbreak? Did they use their high-tech prowess to ensure Beijing was aware of all suspect cases in real-time? Apparently, no, no, and no.

In addition, global warming (and the multiplication of large-scale natural disasters) over the past 20 years is quite worrying. It has been well documented in the USA, for example.

Now comes the time to ensure your supply chain can’t be hit again with the same intensity, right? That’s a logical thought process.

Until last month, we were not feeling a strong pressure from our core clients (who develop their own products) to move out of China. These days, we can see they think differently and are reconsidering where they source their products.

2 sourcing approaches to mitigate risk

Let’s explore the 2 approaches that generally make sense:

1. Geographic diversification

As the current epidemic has shown, the risk is different in different areas:

- There is a lot of concentration of power in Beijing. And yet, local officials still have a lot of power and can respond differently to the same situation.

- Some cities are at the epicentre of the outbreak, while others only have a few cases.

So, having a supplier in Guangdong and a supplier in Shandong for the same product can be helpful.

And having a supplier in Dongguan and one in Ho Chi Minh City is more helpful since these 2 cities have more divergent risk profiles.

There are a few issues with this approach, though.

- These 2 suppliers might still get some of the materials/components from the same city in China. Without visibility into tier-2 and tier-3 suppliers, your entire supply chain might rely on 1 weak link!

- The unfortunate reality is, the business environment in this part of the world is all but transparent. Most importers don’t know who supplies their assembly factories. In some cases, they don’t even know in what city final assembly & packing are taking place…

- A small company can’t split its purchasing volume among several suppliers. And an innovative company doesn’t want to share its intellectual property with two or more suppliers, who could be tempted to become competitors.

2. Simpler and shorter supply chains

If components come from many different manufacturers, the supply chain is complex.

And, if those manufacturers are far away from the market and/or far away from each other, the supply chain is long.

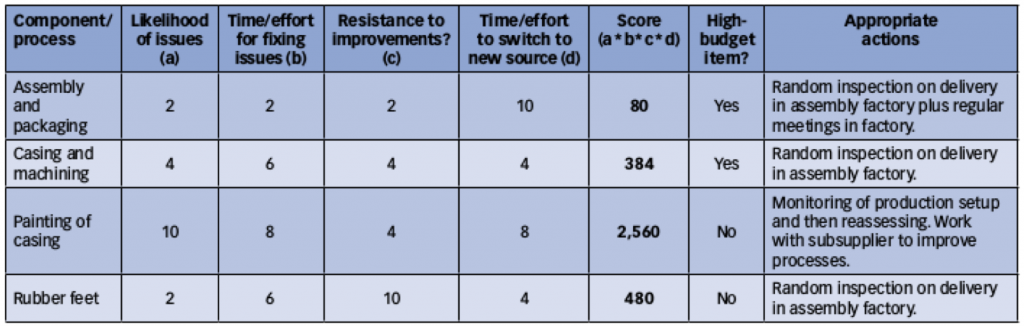

I wrote about the risks posed by long and complex supply chains a few years ago in Quality Progress. And the first step is to know where the sub-suppliers and sub-sub-suppliers are located. For your most critical products, filling out this table for each line on the bill of materials will give you a good idea of the total risk for each product:

So far, few clients tasked us with this type of research & analysis job. Now might be the time to know your supply chain!

Are many companies working on alternative sources in other countries?

Yes, of course. Journalists are starting to find such examples. For example, the Nikkei Asian Review covers this in Multinationals reroute supply chains from China — for good? (h/t to Dan Harris):

With China’s supply chains cut off by the coronavirus outbreak, multinational companies are moving production outside the country or looking for alternative sources for parts.

While these are simply stopgaps to get operations back online, enterprises will be evaluating whether the new destinations offer more competitive costs than China, where wages continue to climb.

Some experts see a possible turning point for Asia’s manufacturing landscape if companies opt not to come back to China.

This article goes on to mention several companies that are working to diversify manufacturing sources outside of China to secure their pressing needs, and that are not sure their business will ever return to China.

I bet many consumer brands are re-evaluating their supply chain strategy, but now is not the time to announce it for several reasons: new sources are not ready to produce yet, and Chinese consumers may be unhappy with brands that let their country down in the middle of a crisis.

If possible, work on a risk-reducing AND value-adding diversification

If your major market is in North America or Western Europe, and if your competitors all make their products in China or Vietnam, what they are selling comes with:

- Long lead times (except if your product is small and high-value, in which case air shipments may make sense)

- Low flexibility, in many cases

- Low transparency and the associated risks: quality, PR, and other nasty surprises

- A “Made in China” tag that some consumers don’t like.

That’s what I’d call ‘faraway sourcing’.

You might be able to take an entirely different approach: either ‘reshoring’ or ‘near-sourcing’… and provide associated benefits to your customers. Let’s look into these options.

‘Reshoring’, in contrast to ‘offshoring’

If one of your products can be made with a very low amount of labor, why not make it in the main country of sale? You will be able to offer much shorter lead times, and some consumers are happy to buy local.

For example, some of our clients purchase plastic toys. Reshoring makes little sense if there is a lot of manual painting involved. But it does make sense for playsets that are injection molded (a process where unloading and visual inspection are automated) and the parts can be assembled & packed in under 1 minute.

The more custom-made the products, the more interesting this approach becomes. One of our clients makes custom cooking utensils for a certain type of restaurant chains, and having a factory in the same country provides a clear competitive advantage (better problem solving, and speed) since the same engineers can:

- Observe the customers’ current practices and challenges, and suggest problem-solving ideas

- Work on prototypes and observe how they are received and used in the customers’ premises

- Ensure the new designs are manufacturable since they are familiar with production processes

- Move the new designs into production while keeping the “design intent” in mind, and get them to market fast

Do you have to do this yourself, and open a new factory? There might already be a few good manufacturers hungry for more orders — search for them first.

‘Near-sourcing’: Serve your market from abroad but by truck (not by ship)

Many companies make products in Mexico or Central America and sell them in the USA and Canada.

Similarly, Portugal, Eastern Europe, and North Africa are major production hubs for Western Europe.

The benefits, relative to China manufacturing, are:

- Lower lead times and minimum order quantities, which in some cases make a huge difference to the bottom line (for example, fashion retailers can re-order a style that is in demand, and are left with less unsold inventory)

- The generally comparable cost of labor, and higher productivity in well-managed factories

- Ability to send the products back by truck if quality issues are detected

- Better cultural understanding (in some cases) and a much smaller time difference, making for easier communication

The benefit of holding higher levels of inventory

Let’s not forget this approach, too. Companies that are sitting on a lot of inventory are in a better position these days.

Most inventory-carrying wholesalers have suffered fierce competition in the 2000s and 2010s. I was once working in such a company (15 years ago), and they went bankrupt around 2010…

However, I have seen a few such companies thrive. One of them, in Canada, has doubled in size every year over the last 3 years. Good merchandise selection, good distribution networks, and a growing economy have led to great results.

What factors to consider, when deciding on the right model for your company?

In 1997, Womack and Jones suggested companies take all important factors into consideration in their book Lean Thinking. (Note: they wrote for companies considering offshoring their manufacturing, but the same factors are at play for those considering pulling production out of China.)

– Start with the piece part cost of making your product near your current customers in high-wage countries — that is: the US, Western Europe, Japan. Compare this number with the piece part cost of making the same item at the global point of lowest factor cost (probably dominated by wage cost). The low factor cost location will almost always have a much lower piece part cost.

– Add the cost of slow freight, to get the product to your customer.

You’ve now done all the math that purchasing departments seem to perform. Let’s call this “mass production math”. To get to “lean math”, you need to add additional costs to piece part + slow fright cost, in order to make the calculations more realistic.

– First, add the overhead costs allocated to production in the high-wage location — costs which usually don’t disappear when production is transferred. Instead, they are re-allocated to remaining products, raising their apparent cost.

– Then add the cost of the additional inventory of goods in transit over long distances, from the low-wage location to your customer. Then, add the cost of additional safety stocks, to ensure uninterrupted supply.

– Next, add the cost of expensive expedited shipments. You need to be careful here, because the plan for the product in question typically assumes that there aren’t any expediting costs, when a bit of casual empiricism will show that there almost always are.

– Then add the cost of warranty claims, if the new supplier has a long learning curve.

– Next, add the cost of engineer visits, or of a resident engineer at the supplier, to get the process right so the product is made at the correct specification with acceptable quality.

– Then add the cost of senior executive visits, to set up the operation, or to straighten up relationships with managers and suppliers operating in a very different business environment. Note that this may include all manner of payments and considerations, depending on local business practices.

– Then add the costs of out-of-stocks and lost sales, caused by the long lead times to obtain the correct specifications of the product, if demand changes.

– Now add the cost of remainder goods, or of scrapped stocks, ordered to a long range forecast and never actually needed.

– Then add the potential cost, if you are using a contract manufacturer in the low-cost location, of your supplier quickly becoming your competitor.

This is becoming quite a list! And note that these additional costs are hardly ever visible to the senior executives and purchasing managers who relocate production of an item to a low-wage location based solely on piece part price + slow freight.

However, “lean math” requires adding three more costs to be complete.

– First, currency risks. These can strike quite suddenly when the currency of either the supplying or the receiving country shifts.

– Second, country risk. These can also emerge very suddenly when the shipping country encounters political instability or when there is a political reaction in the receiving country, as trade deficits and unemployment emerge as political issues.

– Third, connectivity costs. These are the many costs in managing product hand-offs and information flows in highly complex supply chains across long distances, in countries with different business practices.

I hope this gives you the elements to keep in mind when considering diversifying manufacturing sources. The right approach will depend on your situation:

- Do you make 1 product or many different products?

- Do you sell predominantly in 1 country? Do you sell in China?

- Do you simply walk around a trade show, point to a nice sample, and say “I want this in black, with my logo”? (It will be very hard to leave China.) Or do you design your own products? (Much easier to move production.)

*****

Where do you sit on this topic? Have recent events in China forced your business to diversify manufacturing sources globally, or are you ‘all in’ on China? Let me know in the comments, please.

8 Elements of a Low-Risk Supply Chain in China

This FREE webinar will empower you to transform your supply chain in China to reduce risks. Two industry experts, Renaud Anjoran and Paul Adams from Sofeast, talk you through how to gain control over your product’s quality, on-time shipments, long-term pricing stability, and continuity of supply.

Ready to watch? Register by hitting the button below:

I forgot to include 1 data point. In our Dongguan facility, to attract production workers, we had to raise the basic salary by 30%.

Only time will tell if this is going to be temporary, or if market conditions will dictate that it remains “the new normal”…