If you make sure to sit on 6 months of inventory for every one of your major products, you will run much lower risks of being unable to supply your customers with what they need. You might even be able to cut a current manufacturer off and ramp up a new one, without any impact on your customers.

There will be downsides, though. Working capital is expensive. Warehousing and transporting all these goods are not cheap. You may have to write off damaged, lost, of rapidly obsolete materials. (It is simply not feasible for electronic components, food, etc.).

Oh, and you may be unable to sell these products if demand dries up. For instance, warehouses are full of unsold spring/summer clothes these days. And some of those clothes won’t sell next year, as fashion evolves.

So, the question is, how to balance these benefits, these costs, and these risks? This is what we are covering in this article.

Note: This is the fourth article in this series on supply chain risk management. In part 1 I covered “Black Swan events”, in part 2 I covered the business continuity plan, and in part 3 I covered the purchasers’ KPIs.

Examine the inventory all through your supply chain

There may be many nodes in your supply chain. If each one of those nodes holds inventory, obviously it all needs to be added up.

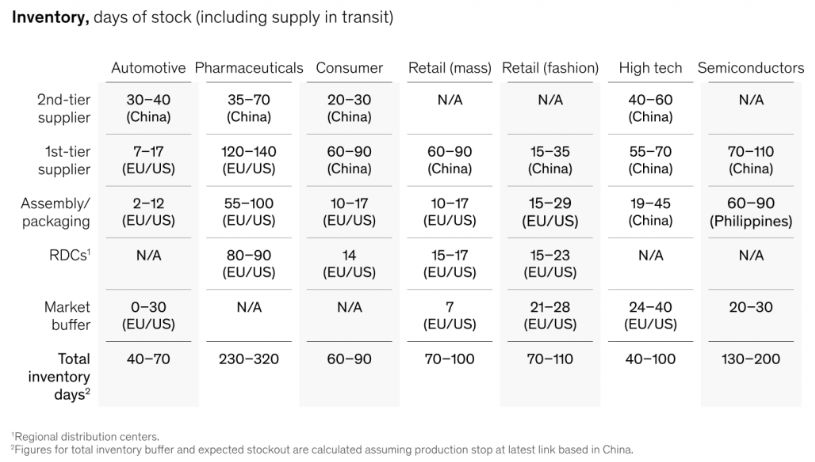

McKinsey did a nice job compiling these data for 7 broad industry verticals:

Here are a couple of implications of this table:

- If one of the 2nd-tier auto part suppliers in China is hit, the assembly plant in Europe or North America has to stop within a couple of weeks. That’s what happened in March 2020.

- If the assembly plant in China for a high-tech product is hit, consumers may be out of products in a few weeks (or earlier if they anticipate that shortage and do a run on the shops). This has not happened so far, but many people were afraid of it earlier this year.

In other words, higher inventory leads to a lower risk of discontinuity of supply.

Good news: there are already many mathematical models

Numerous chain optimization software has appeared over the years. And they are more and more popular in companies of a certain size.

Here are a few statistics about this, from Supply Chain Dive:

The most recent MHI Industry Report found 40% of supply chain professionals say their organizations are currently using inventory and network optimization tools in their operations and 34% expect to do so within the next two years.

Amazon and other large retailers have developed sophisticated algorithms to help them determine where to put inventory. Nike even acquired a company, Celect, to help improve its inventory management.

However, for the purpose of this article, I want to cut through the complexity and cover the main factors to consider.

Even better news: there is a good model that is relatively easy to understand

After the disasters of 2011 (Japan tsunami, Thailand floods…), an MIT professor and a representative of Ford Motor Company set out to create a model that is not overly complex and that aims at:

- Identify exposure to risk

- Prioritize and allocate resources (where to hold inventory, in what quantity, for what SKUs)

- Help develop the right mitigation strategies

All this is summarized in this webinar. The description of the model starts about 13 minutes into the video:

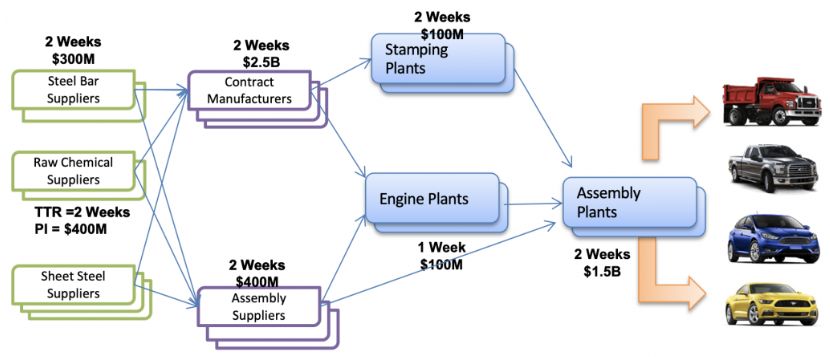

First, start mapping the facilities along the supply chain, and collect some information about them:

- What is time to recover, for each facility, after an interruption of activity?

- What is the impact on your company (e.g. higher costs, loss of revenue…) of a disruption at each facility?

Here is an example (from their slide deck):

Now, what suppliers have the highest impact on your company if they go down? These represent your highest risks.

When Ford did this analysis, some suppliers representing a very low spend involved very high risks.

Another interesting metric to track is the time to survive (the maximum time for your company can keep fulfilling demand after one of the upstream facilities is disrupted).

Here are two interesting implications:

- If time to recover > time to survive, and there is no way to have another facility produce that same product, it can lead to a discontinuity of supply, and that cost depends on the impact on your company.

- If time to recover = time to survive, some parts may have to be shipped by air rather than by sea (much higher cost).

I won’t cover the details, but a good model includes profit margins, volumes for each part, and so on and so forth. If you are curious, you can get see some of the main formulas in the last slides of their deck:

You can get the slides from Inform here.

How all this leads to better decisions

Based on estimated market demand, on available resources, and on the risks identified above (and their financial impact), a good model helps your company allocate the right levels of inventory for each product.

It will also allow you to:

- Decide when and where expediting shipments will be necessary

- Book shipping capacity in advance (to pay a lower rate and raise the chance of actually reserving that capacity)

- Decide where a backup supplier is needed, or additional inventory needs to be kept at all times (that might have to be in one central location, as Simchi-Levi suggested in this interview).

- Make sure purchasers are aware of the highest-risk suppliers and geographical areas, and to have them act accordingly: lining up backup suppliers or trying alternative materials, etc.

Michel Baudin did a nice summary of this webinar, too, and he points to certain difficulties. As often, implementation may not be simple and obvious.

Re-inventing your model for bringing goods to market

Trade war with China. Inability to travel to faraway factories. Rising production and shipping costs. Shortage of working capital. Changing consumer habits, and difficulty of forecasting demand long in advance. Is your company thinking of changing its model?

Some companies have found that producing relatively close to the market (Mexico for the USA, Poland for Western Europe, etc.) allowed them to contain their total costs and to be more responsive to market demand.

At the end of the day, most of these discussions about the levels of inventory are based on the assumption of long and complex supply chains. The first question would be, could you get away from that model?

P.S.

Learn more about Supply Chain Risk Reduction Strategies here.

Join me in a webinar on July 15th: ‘CRACKING SUPPLY CHAINS,’ with Belgium-Luxembourg Chambers in Asia

In this webinar, I’m on the panel with 2 other guest speakers and the topic is to investigate the cracks that have appeared in supply chains over the last few months during the coronavirus pandemic.

In my section, I’ll be discussing reimagining and reinforcing your supply chain to reduce risks in the future.

It’s just $25 for non-members and takes place on Wed, 15 July 2020 from 11:00 – 12:15 BST, so

Register to attend here 👉👉 https://www.eventbrite.sg/e/cracking-supply-chains-tickets-112561390148 👈👈