Many people work hard to get to a working prototype that looks good, then they think it’s a production ready prototype and can just be passed to a manufacturer.

However, as I wrote before, there are many challenges when going from prototype to mass production. In some cases, there is still an enormous amount of work left to do.

Since we sign strict NDAs at my company Sofeast, we can’t use our clients’ products as examples. But there are plenty of books that describe good examples. Let’s take 2 examples that illustrate very different situations.

Example 1: Getting to prototype is fast, but getting into production takes much longer

I read the book ‘Cutting the Cord‘ recently and I enjoyed it.

It tells the story of the development of the first mobile phone at Motorola, the DynaTAC 8000X.

It actually went pretty fast.

The program manager worked with industrial designers (from within the company) for about 3 weeks. They even had the luxury of designing several good concepts, such as physical renderings and picking one.

It turned out that the initial physical rendering was way, way too small to include all the electrical parts, so the general form factor was kept intact but the prototypes grew in size, to the point where it got called “the brick”.

In about 3 months, they got together a prototype of their DynaTAC model:

Our immediate goal, achieved through a harried three months of development, was to show the FCC that competition could better spur innovation than monopoly.

How was it so fast, for a ground-breaking new product? The program manager was allowed to pull resources from various internal labs (many of which had already worked out some technologies needed for that prototype), and it was made the company-wide first priority at the time.

One report asked whether the DynaTAC would reach Australia. “Of course”, I said. “Try it, but I’m sure you know it’s the middle of the night there.” She called and awakened her mother, astounding everyone in the room.

And then… the long road to mass production took another 10 years and about 100 million USD before market launch!

Ten years after my New York City sidewalk call, the first commercial cellular phones went on sale for nearly $4,000. That would be like buying a phone today for $10,000.

Why did it take so long?

- There were regulatory hurdles, as the FCC freed up the required radio spectrum frequencies very slowly.

- The TRL (Technology Readiness Level) was barely at TR5. They had installed radio transmitters around the demo area. Getting to TR8+ took a long time.

Example 2: Getting to prototype is quite slow, but getting into production is much faster

This example comes from the book ‘Leap: How to Thrive in a World Where Everything Can Be Copied‘.

It includes the story of the R&D attempts at developing a washing formula that did not make the fabric feel coarse. That’s the story behind the very successful launch of P&G’s Tide brand.

Early attempts were pretty much abandoned by the company:

After holding out for 10 years, and spending more than 200,000 hours on mind-numbing tests to get the formula right, the research team was all but quietly disbanded with key personnel reassigned elsewhere. Managers shunned their association with the failing venture. But there was one single-minded scientist, a maverick who refused to give up on what would later be known as Project X.

David “Dick” Byerly, who eventually filed the key patent for Tide, continued with his line of research at a time when the management had explicitly ordered a phase-out.

That tenacious researcher kept working on it through World War II, leading to a breakthrough:

The gamble paid off, In 1945, Byerly identified sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP) as the ideal builder.

An internal demo showed it represented a great improvement over products that were on the market at the time:

The formula worked and delivered beautiful results. […]

A product demonstration was staged. Among the attendees were Richard Deupree, the company’s president; Ralph Rogan, VP of advertising, and R. K. Brodie, VP of manufacturing and technical research. The three had no doubt about the market potential of Project X. The only question was the timetable for the commercial launch.

From there, things went fast.

For the first time, a P&G brand was launched without the usual blind tests and other pre-launch validation stages, as an effort to catch its competitors by surprise and grab a dominant market share.

It was introduced on the market in 1946 and became the best selling detergent in 1949.

Why did it get into mass production so fast? The company had a lot of experience making laundry detergents, and setting manufacturing up did not take years of work.

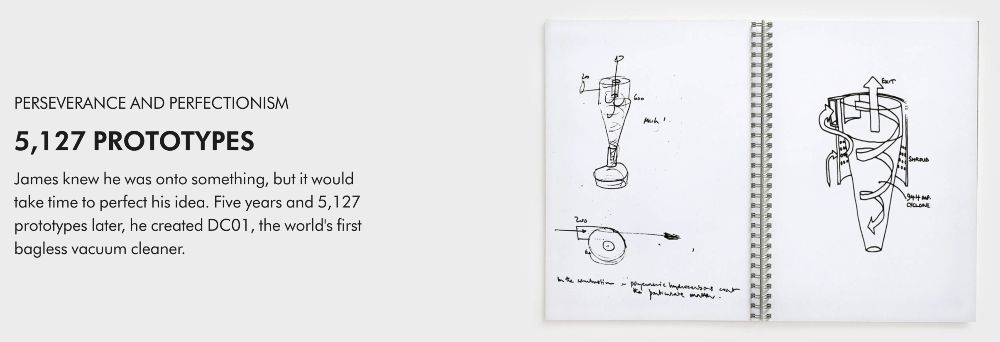

Dyson’s lengthy prototyping development is another example

Another example of slow prototype development and then faster production, in the world of electro-mechanical products, would be Dyson’s 5,000+ trials, over 5 years. This certainly wasn’t a production ready prototype at the start!

I wrote more about that case study here.

(Image credit: James Dyson Foundation website)

Conclusion

These examples demonstrate that having a working prototype doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re holding a production ready prototype. In fact, there may still be a lot of work to do before you reach that point.

As I wrote here: A Textbook on Design for Manufacturing and the NPI Process (EVT-DVT-PVT), there might be 6-10 months of work to get your initial product concept into mass production!

What do you need to know about prototyping and being production-ready? Let me know by commenting, please.

Are you designing, or developing a new product that will be manufactured in China?

Sofeast has created An Importer’s Guide to New Product Manufacturing in China for entrepreneurs, hardware startups, and SMEs which gives you advance warning about the 3 most common pitfalls that can catch you out, and the best practices that the ‘large companies’ follow that YOU can adopt for a successful project.

Just hit the button below to get your copy (please note, this will direct you to my company Sofeast.com’s site):