So, your Chinese manufacturers ask for price increases in the 10-20% range. Are you unsure of what to answer?

So, your Chinese manufacturers ask for price increases in the 10-20% range. Are you unsure of what to answer?

Here are few tips.

First, tell them you don’t understand

You might have a few arguments in your favor:

- Maybe your volumes have increased. Shouldn’t you be entitled to lower prices?

- Maybe you have been a regular customer and orders have been pretty smooth. Shouldn’t they take this into account and give you favorable pricing?

- Maybe you can get other suppliers to quote lower prices for similar volumes. Shouldn’t they look at the market price at adjust their offer?

The strategy here is to refer to general business principles (without closing the door for a price change), and see what the factory responds. After all, it is up to them to give a detailed justification.

Second, center discussion around hard data

You will need to evaluate their cost breakdown (very roughly). For example:

- Labor might represent 20% of their total cost

- The main material might represent 50% of their total cost

(The rest of the costs lie in equipment, energy, logistics, sales & marketing, etc. but you probably don’t need to mention those.)

If the factory wrote “salaries went up 20%” (which is possible), the total cost is only up by 4% based on the above estimate (20% x 1.2 = 24%).

I am taking this example because Chinese manufacturers often use the rise in wages to justify price hikes. But you need to be prepared to fight three other excuses.

1. If the supplier says the cost of the main material has gone up

You should search the trend on the international market.

For example, for aluminum, you will find that the price has been going down steadily (click on the image to enlarge):

In this case, you can probably suggest that your supplier finds a better source rather than passing his inefficiencies on to you. If they respond that their price has increased, you can suggest to involve a sourcing agent to double-check on this.

Note that the international price is not the price manufacturers pay within China, but the trend should be similar… And you are providing data, so it is up to your supplier to do the same.

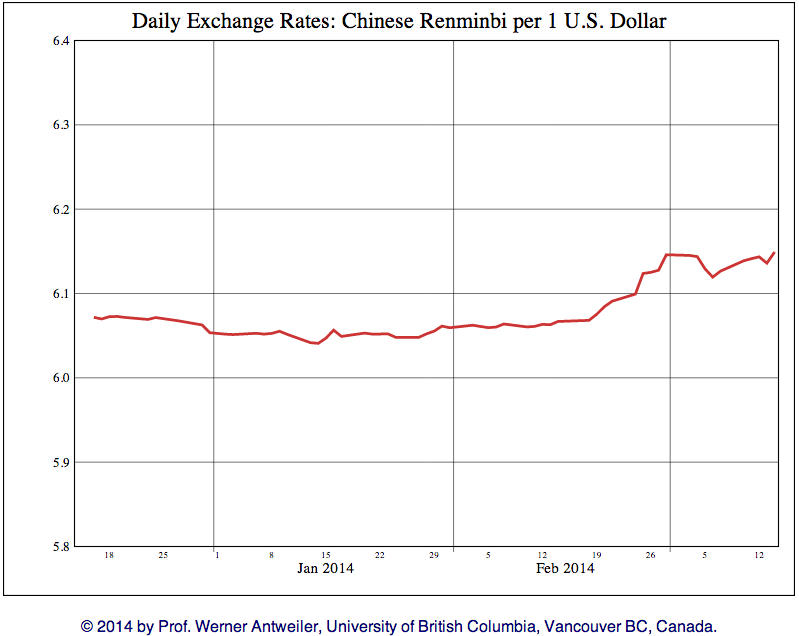

2. If the supplier says the USD/RMB rate has gone down

Once again, you should look up what the trend looks like.

Over the past 3 months, actually, the RMB has lost some of its value in front of the dollar:

Is the long-term trend clear? No. But now is definitely not the right time for them to invoke the exchange rate as an excuse for higher prices!

3. If the supplier says your quality standard is too high

Ask them how it impacts costs.

If it slows production down, ask why they quoted too low last time, and why they waited for you to send a re-order before they told you about it.

If there is a high scrap rate, ask them how high it is for your production, and how high it is on average. To test if they are serious, ask if they are ready to pay consultants to come and fix this problem. (You can say that you are willing to pay for the consultants’ fees).

A note of caution

In any case, don’t push back in too firm a manner. Keep in mind that your manufacturers have a very primitive accounting system, and they don’t really know what drives their costs.

If they feel that your orders are not profitable, they will find a way to cheapen your product. And it will probably cause quality problems. This is not what you want!

If you feel they are gauging you, though, you can mention that you will start looking for another supplier for orders to be in production next year. You can use fear of losing your business to your advantage, and keep price increases moderate.

What do you think? Any other tips?

I think , The increasing % should base on last order , for example : if last order was in 2010 or 2011 , then price should + 20% ( or more) in 2014 . But, if last order was in 2013, then + 5 % to 10% in 2014 is enough , but some client already SAY NO even just 5-10% , they said that they will find another fty if we increase the price .

.

I was actually thinking about something the other day, that you mentioned in your post :

“Labor might represent 20% of their total cost

The main material might represent 50% of their total cost”

I know this is just an example, but would you say that a very general rule of thumb for analyzing a BOM would be to assume 20% labor and 50% material costs for production in most industries?

No, you really can’t apply this across the board.

A factory making cheap garments (with cheap fabrics) will have a higher labor cost.

A factory that assembles electronic products will have a higher material material cost.

A factory that die-casts gardent tools will have a higher electricity bill.

And on and on…

Good post, Renaud.

Another strategy which I have used is to explain that the price has become too much and that means I have to redesign the product to make it cheaper. This will require 3-4 rounds of sampling and delay further orders for 6-9 months while I work on the new design.

Given a choice between making an old product now (easier to do since the factory has done it before) vs a new product later (which requires time and energy and may not result in an order) oftentimes a factory will adjust their price increase to take into account these factors.

The most important part of this response is that you are not bluffing. I only use it when it really means a big price increase would require me to redesign for a cheaper alternative.

That’s a good one! Thanks Callum.

Regarding the “note of caution” in point 3, asking your factory to hold the price and inadvertently causing your factory to cheapen your product should not be taken lightly.

Unless your factory was not making a profit before, it is easy for a factory to hold a price. They simply make less profit or break even. It’s not difficult at all.

The problems arise when unexpected things happen. If the factory has fluctuations in production, from delayed raw materials or not enough hands on deck, whose products do you think they will save first? They will divert all time and resources on the profitable products, leaving yours to suffer. They didn’t deliberately cheapen your product, but they are simply allocating their resources in the best manner. Maybe they’ll divert all their QCs on the profitable production, leaving your production to go without QC.

Yes, that’s very true.

Nice theoretical points! But in reality this would bring distrust among us & manufacturers. In my opinion we should get to know more about the global trend and know everything in heart and need not to challenge manufacturers. Just like you feel the prices in the supermarket are too expensive for you and you would not challenge the supermarket, you may just simply choose to buy or not.

I had challenged manufactuers and I did suffer and lose many invisible good things, and lost my reliable supplier too. So, the price is not just for the product.

Thanks for sharing anyway.

Well, if you can afford to pay the price asked by reliable suppliers, you certainly don’t need to read this article and challenge them. But, if you feel you are being cheated, at least you should question where cost increases come from. If it forces you to look for another, cheaper supplier, I think it is fair to challenge the current supplier — it is actually in their interest.