Chinese factories hate small orders. And, when they do get a large order, they hate having to cut it in several small production batches.

There are several reasons for this:

- Most manufacturers here pay their direct labor by the piece. So operators love to work on the same thing for several weeks – they get used to it and slowly gain in productivity. If they start and stop, they don’t have time to get used to it, and there is a direct impact on their pay.

- The managers and their engineers have to spend time setting up the lines, the tooling, and so on. The warehouse has to bring the materials. Since they usually have an immature planning system, this whole process takes them time and is a bit of trial-and-error. They hate that extra complexity.

However, there is a rule we have observed, and in which we strongly believe, when it comes to making a new (customized) product:

No pilot run = high probability of quality issues and efficiency issues in the first production batch

Do Chinese factories all say no to a pilot run? Of course not. But they will probably push back a bit.

The fact is, pilot runs are not a rare animal. They are a must for those manufacturers that work for many large companies buying medical devices, electronic products, aerospace components, or automotive parts. It is part of the APQP process (the state-of-the-art approach to new product introduction). And it should also be part of your process if you develop new products.

I am going to explain why in this article.

First, what does it mean to do a pilot run?

It simply means launching a very small production run (a few tens or hundreds of pieces), to be made in EXACTLY the same conditions as mass production:

- Same materials

- Same machinery, tools, jigs, and fixtures

- Same operators working off the same instructions

- Same process controls

As part of the pilot run, engineers should observe the run rate and the defect rate, and note any other issues. And they should work on improvements – often in processes, in training, or in incoming component quality.

If something totally fails, the worst case is that the few pieces made have to be disposed of or reworked. Think of it as a sandbox where issues are found without huge consequences.

We have seen large batches entirely thrown to the dump because of an issue that was noticed too late. This is bad for the buyer and bad for the producer!

That’s why we strongly suggest that importers who develop a new product make this step a MUST.

What are the benefits of a pilot run?

In other words, what cannot be done by simply looking at a prototype and thinking “how to ensure production is smooth right out of the gate”? A do-on-a-small-scale-and-adjust approach is indispensable for several reasons.

1) Planning a production line with respect to build order sequence and where components are fed into the line and where test stations are is a critical step to getting the product flow right. It is not until products are run down the line, however, that the line arrangement can be reviewed to see if the line is set up properly.

2) Training the people needs to be done before they start working on mass production. An important aspect here is to create clear and concise work instructions for staff to follow. It is also good practice to train more than one staff for any one process, particularly on the more critical workstations.

3) Making sure the people know what they are supposed to do is another benefit of pilot runs. Every single person involved with building the product should know what to do and when to do it. Watching them do it consistently is the only way of ensuring this.

4) Test areas and equipment readiness can only be established once the product is built on the production line. It will become very apparent if a piece of equipment is in the wrong place or is the wrong type or size, for example, a bearing press not powerful enough to press in bearings. The factory needs to ensure all the test equipment and all the relevant test stations function as they should. And they need to check that bad products are caught — it is important that bad products do not get pushed down the production line to the next workstation!

5) Testing the processes at ‘run at rate’ to make sure that you can make the product at the rate you are supposed to. The main purpose of this action is to verify the output of the production line at full speed – from pulling raw materials to packing the goods ready for shipment. If the line can only make 20 products per hour, you can make your projections… It will take about 100 days for this one line to manufacture your 10,000 pieces order if no improvement is made! Better to know about this now than later, isn’t it?

6) Stress the processes, stress the testing, and stress the people that will be making the product to really see if what you have set up is correct. If your timelines mean the line should be able to make 60 pieces per hour, challenge the factory to get to at least 50 in the pilot run. (This is what car assembly factories do, but Chinese factories usually won’t have the patience for that.)

7) Identifying failure modes and production issues is at the heart of the pilot run. In mass production, the obvious issues are usually detected, whereas subtler issues (which might also have strong consequences) are often missed… or ignored by production operators. Remember, they are focused on pushing products down the line as fast as possible.

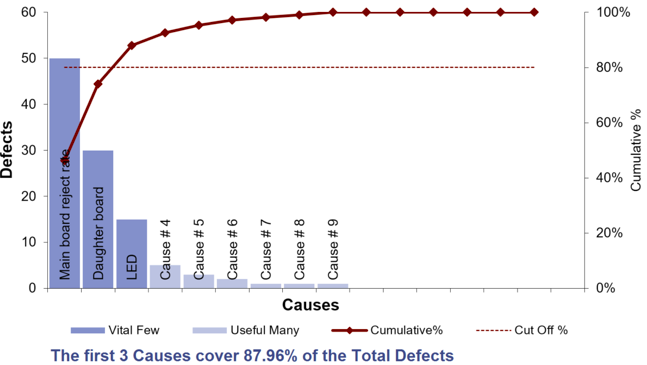

Typically, many issues are identified during the pilot run. It is common to show them on a Pareto chart in order to identify what to work on first.

How to fix these issues once and for all? By opening corrective action plans and following them through, as I explained here. NOT by simply reworking the products (otherwise the same issues will come back again).

8) Control measures detailed in the control plan (if the factory has prepared one), or as conclusions to FMEA analyses (again, if the factory took that pain) should be monitored and verified. Unfortunately, 99% of Chinese factories have NEVER performed those types of exercises. Again, they wait for problems to come up rather than doing the hard work up front.

9) Final step before production — this is the last chance to make changes to the line layout or processes, or even to the design if design issues have been found. Remember, it is much less costly to correct problems at this stage than in mass production.

—

The output from the production pilot run is the authorization to go into mass production. And a lower chance of finding serious issues that will cause long delays and/or poor quality.

Hopefully, you can now see the importance of conducting a pilot run on every new product!

Are you currently starting the new product introduction process, or having some issues getting a product that is being produced in China to market? Our guide over on Sofeast can help show you the process you should follow for success: The New Product Introduction Process Guide for Hardware Startups.

I fully endorse the suggestions in this article. A full, production representative pilot run is essential to prove out the production process.

As is suggested in the article, many Chinese factories resist making the commitment for a full pilot. Often this is because they don’t really understand the philosophy – they think that the goal is to produce a sample part– not to prove the capability of the process. Even if this sample is done from the production tools, in the production process, a run of 3 – 5 pieces just doesn’t get the job done.

One compromise I have made to get some factories to do this is that I’ll request 5 pieces to be fully checked in the pilot run. I’ll allow them to run, say, 2 – 3 pieces as the initial sample; I check the 2 – 3 pieces. If I approve them, then they proceed to run a 100 or 200 piece pilot run. I agree that as long as the balance of the pilot run are equal or better to the 2 – 3 pieces, I’ll accept the pilot run. And, they still need to do a thorough check of every characteristic for 2 – 3 more pieces sampled from the pilot run.

One other behavior that has baffled me is the willingness in this process to fill out inspection forms with the answers that they know I want to see, even if they are totally impossible. For example, some of my products require destructive weld tests. The factory will report the results from destructive weld tests done on all 5 samples… and then provide the samples in perfect condition. So it’s obvious that those destructive tests weren’t done! In other cases, I see dimensions reported when I know that the factory has no measurement equipment capable of variable measurement, but only go-no go gages. Where did these numbers come from, I ask??? No answer…. no one will admit that they were a total fabrication!

So, if at all possible be there, or send a qualified third party inspector, to see the checks done.

Good luck!

Brad

Thanks a lot Brad for your comments.

You are right, Chinese manufacturers, in their vast majority, don’t understand the reasons for a pilot run.

Thanks for sharing an approach that works — I can see how it helps when there are lots of dimensional checks or time-consuming tests.

And regarding the fabricated inspection reports… Yes they see this as useless paperwork. It is their “show the right info and pass the test” mentality. Very hard to avoid. And sometimes the importer’s own ‘supplier quality engineers’, who are too much in contact with factory managers, also consider this as normal.