Does it necessarily cost more to reduce the number of defects? That’s a good question in the sense that it brings up different responses from different people.

Does it necessarily cost more to reduce the number of defects? That’s a good question in the sense that it brings up different responses from different people.

I am going to expose a few very different mindsets about the whole “quality” concept.

The traditional mindset that is prevalent in China

If you ask 99% of Chinese manufacturers, they will say “of course, it will cost more to reduce the proportion of defects”.

They think there are only two ways of increasing the quality standard:

- More time spent on writing and enforcing procedures

- More manpower spent in inspection activities

Importers use statistical quality control standards based on AQL limits. If a buyer sets a tolerance tighter than what is usually considered “normal” for general consumer goods, the supplier generally raises prices.

What is wrong with this mindset? It is 100% reactive, 0% proactive. There is no initiative to improve design & production processes.

It is a very “old school” approach. And there are many counter-examples.

A more sophisticated vision

A high defect rate is actually quite expensive. It is at the root of the “costs of poor quality“.

Here are a few examples of such costs:

- Scrap or rework

- Re-inspection / re-testing after a failure

- Disruption of production planning to address an urgency

- Expediting and/or discount given to customer

- Loss of customer confidence in the long run

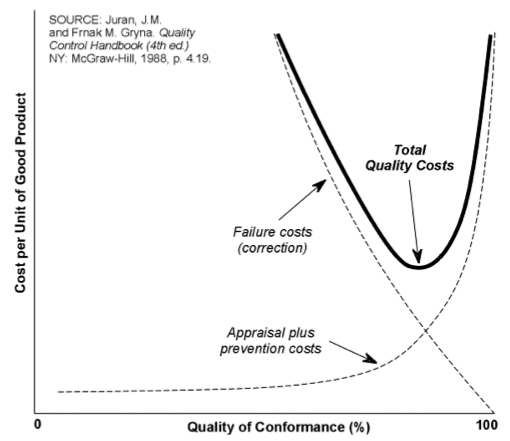

Juran, one of the great quality thinkers, summed it up nicely with the graph below.

- Reducing the defect rate pushes the “costs of poor quality” down and benefits the bottom line…

- … But after a certain point the cost of preventing and catching defects becomes so high, it offsets the costs of poor quality.

How I think about this

I like Juran’s cost of quality graph. And it is important to note that the point where the two curbs intersect (when cost of quality = cost of poor quality) is not in a fixed position. It can move to the right, and allow for low-cost AND high-quality production.

In the book Gemba Kaizen, Dr. Imai describes a soldering workshop in Japan that employed 17 housewives from nearby farms. This company drove its defect rate from 3 percent to 50 parts per million, without automation and without investment.

Here are ways to decrease rejects without increasing costs:

- Simplify the material and information flow

- Design products so that they are less complex to make and less likely to be defective

- Try to improve each process step, document the new procedures, and train the operators

- Accelerate the flow of production, to get finished products earlier and detect problems as quickly as possible

- As soon as a problem is detected, look for its root cause and implement corrective actions

- Set up fool-proof devices (poka-yoke) to prevent defects at the source, when possible

- Make operators feel a certain “ownership” of their process (JKK), and have them do a “self quality check”

All these actions improve quality without increasing the average unit cost.

When will most Chinese manufacturers understand this? When will they make the link between a better production organization and better financial results?

The change can only come from the top of the organization, and unfortunately I suspect the head manager / owner of the factory is more interested in wining and dining business partners than reading books about QC.

Yes, that’s precisely the problem.

Callum’s comment is on target; to add a thought, the laoban is unlikely to read books about QC, but might change when a business partner or peer credits good QC for his success.

One of our suppliers “got religion” on quality after finding a new sub-supplier, who had a great implementation of 5S. Once he saw their plant, he decided he wanted his factory to be as good, or better. He’s made rapid progress, and he’s now my best supplier in China.

Aside, though, we can hardly criticize the typical Chinese business owner for moving slowly in this area. SPC techniques were invented between WWI and WWII; popularized in Japan by Deming, Juran, and others right after WWII; other more sophisticated approaches such as TQC/TQM followed; but it took decades, and the wounds of fierce competition from Japan for many US manufacturers to get the message. I believe Deming himself said that adopting a quality mindset was optional… but that survival was also optional.

That’s a great reminder, thanks Brad.

But many manufacturers already have “wounds of fierce competition” here. Unfortunately these wounds are inflicted by other low-wage producers, not by a high-wage country that has adopted superior principles and tools. I guess it focuses their efforts in the wrong direction…