Quality inspectors in different companies work in different ways. One important difference lies in the way they report their findings. Some don’t report anything in written form, while others spend 2 hours a day doing paperwork.

Quality inspectors in different companies work in different ways. One important difference lies in the way they report their findings. Some don’t report anything in written form, while others spend 2 hours a day doing paperwork.

I can’t reject any of these extremes. They might make sense in their respective contexts. But, from my observations, spending 1-2 hours a day on reporting is often motivated by a need to “cover one’s a**” and is mostly a waste of time.

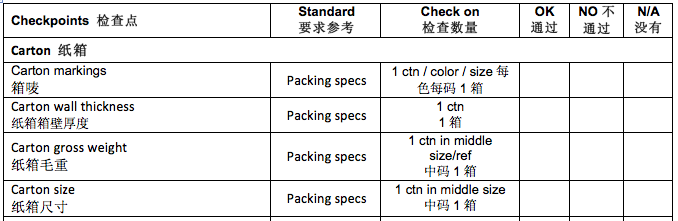

As I wrote before, the best practice is to integrate the checklist into the reporting form. This way, the inspector has to fill out his form and follow the checklist at the same time. Here is a very simple example that takes virtually no reporting time:

But I see many companies forcing their inspectors to write down every measurement/testing result in detail. It results in entire pages of results that take hours to record. Then a manager has a look through these pages, count the number of issues (i.e. findings out of specification), and takes a decision.

If statistical studies are done, recording precise numbers is important. But in 99% of cases there is no such analysis.

I recently read a classic article about the costs of excessive administrative processes. It highlights the danger of giving too much importance to recording findings in detail:

[A] way to improve transaction based overhead is to reduce the “granularity” of the data that are reported. Every manufacturing system embodies decisions about how finely and how frequently transaction data are to be reported. It makes no sense to process more data than needed or more often than needed.

One company, for example, found that its quality transaction system was collecting and keeping quality data on every possible activity—despite the very poor quality of its products. The quality department often complained that it never had time to analyze the data, which just sat in file cabinets and computer files, because it spent all its time collecting. By focusing on the few key areas where most of the quality problems existed, the department was able to improve quality dramatically while it reduced costs. It processed quality transactions more intensively in the key areas and much less intensively where things were running smoothly.

I see this a lot in Chinese factories. Maybe it also takes place in your company:

- Do you spend equal resources monitoring factories/processes that have shown very different levels of stability in the past?

- Do you spend too much manpower inspecting and not enough on implementing improvements?

In many companies, technology has made data collection much easier, which makes this a non-issue. For example, many machines collect and record data about special characteristics (e.g. heat, speed, etc.), automatically calculates their capability index, and emit a warning when they are getting out of control.

Unfortunately, this is not the reality in which quality control is done in most Chinese factories. Human inspectors still need to be dispatched to manufacturing plants that can’t be trusted to collect and provide truthful data. Mobile applications, tightly linked to automated readers (e.g. barcode scanners, digital calipers…) are the best hope to collect precise data quickly and to show it in a concise report.

Your Blog is excellent!