Over the weekend, I read a book called Risk: a User’s Guide. The authors, which include former general McChrystal, make an interesting point about the use of probability.

First, let’s look at the traditional approach to quantifying risk

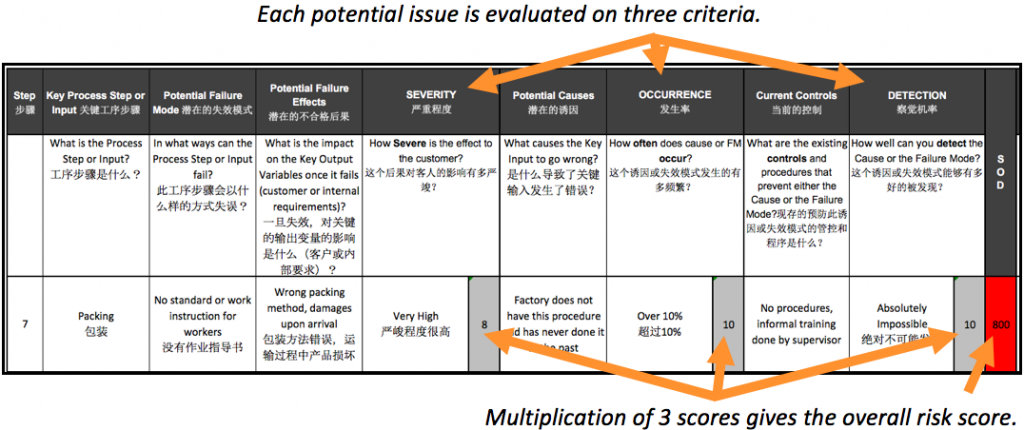

The general approach to assessing risk in quality circles is based on this equation:

Risk = likelihood of an occurrence x severity of that occurence

And practitioners often add a third factor: the ability to detect the risk. Most process FMEA forms include a column for “detection”.

Note: in fact, the ‘detection’ factor is useful in driving action (putting in place controls, and improving the control plan). However, for various reasons, it is ignored when one tries to approach risk in a more scientific manner.

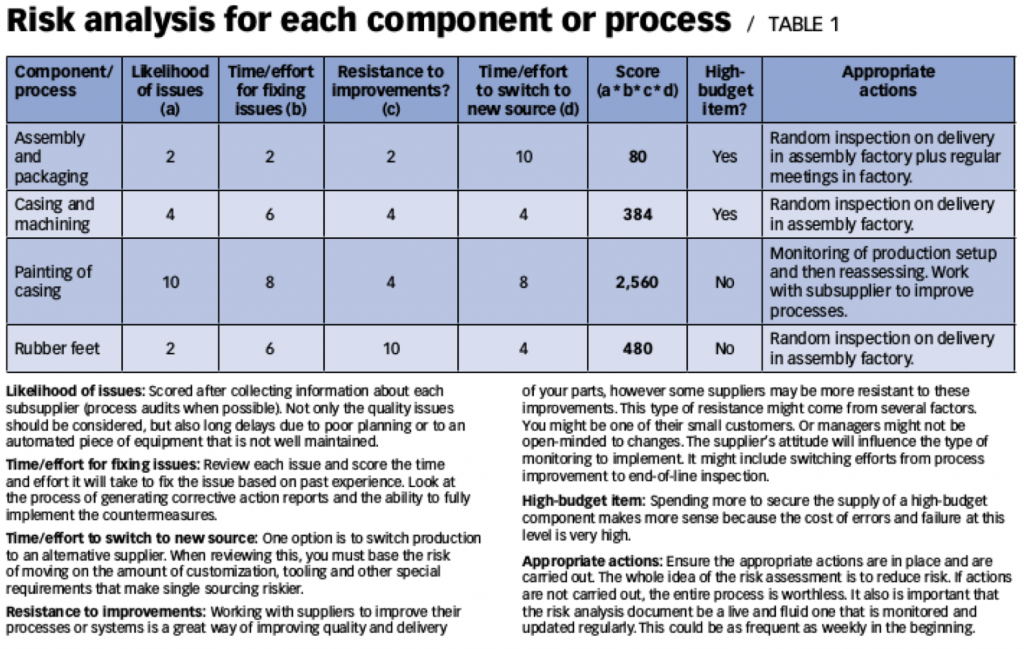

We also included it in a column about likelihood in our 2016 article about supply chain risk (published in Quality Progress):

The rationale for the consideration of likelihood is simple. If ‘hazardous situation A’ is expected to happen once in the lifetime of our known universe, while ‘hazardous situation B’ has been observed every few months, it makes sense to spend more time mitigating ‘B’ if all else is equal.

There are two weaknesses in this approach:

- As demonstrated in The Black Swan, people are not great at estimating probabilities of low-likelihood events. And mathematical models have a really, really bad track record of doing so.

- Experienced quality & safety professionals often look at the very-high-severity failure modes first. Then, they look at likelihood and detection, and at the multiplication score that points to priorities. Letting one’s attention be guided by a dumb formula is dangerous.

Now, what does a retired four-star general of the US Army think about managing risk?

McChrystal believes the focus should be on building a stronger “risk immune system”, rather than spending time quantifying the amount of work, prioritizing potential failure modes, etc.

And he is not the first one to write about this, it appears:

The art of war teaches us to rely not on the likelihood of the enemy’s not coming, but on our own readiness to receive him; not on the chance of his not attacking, but rather on the fact that we have made our position unassailable.

– Sun Tzu, The Art of War (written around the 5th Century BC)

If quantification is needed, it looks like this:

Risk = threat x vulnerability

And McChrystal’s main analogy is that of the human immune system. The immune system detects, assesses, responds, and learns.

The author stresses how a well-functioning organization, which makes good decisions and has strong execution, tends to be much better at mitigating risk.

And good execution is extremely important. Much more than forecasting hazards and planning for how to respond to them.

The authors draw on two recent examples to drive this point:

In the case of COVID-19 and Hurricane Katrina, HHS and FEMA conducted two separate exercises that predicted the risks of an imminent global pandemic on the one hand (Crimson Contagion), and a hurricane that would hit and devastate New Orleans on the other (Hurricane Pam).

Both exercises were conducted before the respective crises occurred–and eerily predicted the circumstances that would later arise when COVID-19 droplets dispersed around the globe and when Hurricane Katrina’s winds whipped on New Orleans’ famous Bourbon Street.

The imminent nature of the threats, as well as the requirement of making decisions and executing actions, were both understood after the exercises were completed, but in both cases political courage was lacking and there was weakness in management to react as the situations demanded.

The authors also suggest that adding regulations doesn’t necessarily have a positive impact.

Large companies were forced to hire a Chief Risk Officer after the high-profile bankruptcies of Enron and Worldcom… and yet it didn’t prevent Lehman Brothers from mismanaging risk to the point where they went out of business, because of very poor processes & organization.

*****

In a nutshell, analyzing pitfalls, running simulations, and writing disaster prevention/recovery plans are great, but those are NOT the core activities to ensure an organization will mitigate risks and survive. Good management that sets up a sound organization and great processes is what’s often missing.