You work with a supplier based in China. You believe they can do a good job if you manage them appropriately. But you can see you are taking a risk in working with them (the maturity of their management systems, their recent performance, and you can see obvious warning signs.)

Is this your situation?

What should you do? Is there a way to reduce your risks and develop this ‘not-so-great’ supplier so you can count on them?

Here is the general advice I’d give you.

Understanding the nature of the risks

First, take a step back. What might happen?

Based on our experience, there are 5 big sources of quality issues:

- You (or the trading company you work with) picked a factory that doesn’t even know how to make the type of product you purchase, or that works mostly for customers that require a very different quality standard from yours. Run away…

- The factory doesn’t manage quality in a systematic way, so there is always a risk that the managers are not looking closely at the situation and some big mistakes occur. A quality systems audit will reveal if that’s the case.

- There is a risk of conscious “quality fade”, often around the 3rd or 4th batch, with certain suppliers and in certain situations. If they see they could be making more money with a quick shortcut, for example buying a cheaper plastic polymer or refurbished electronic components, it is very tempting. This has been a recurring problem with Chinese suppliers, but thankfully it seems to be getting less common.

- There is the risk of a sudden and large change at the factory. They might lose a key customer and get in a cash crisis, the owner might decide to sell, they might owe a lot of money to a supplier/lender and it might lead to a big clash, etc. When this happens, and it is combined with point 1 (no solid management systems), the situation can get really bad. Think of a small restaurant that loses its good chef and just hopes the remaining cooks can keep getting the same results…

- There is a clash in the relationship, or you owe them a lot of money, and they end up seeing you as an enemy. They may take actions that will hurt both you and themselves to reduce their perceived exposure to risk.

In cases 1 and 5, the solution is usually to switch to another supplier as fast as possible. In case N0. 4, you need to keep monitoring the factory’s situation.

That leaves us with risk profiles No. 2 & 3 — let’s dive into what you need to do.

Make sure you get the basics right

This should go without saying, but I am shocked at how often it’s not the case. Here are some of the basics you need to get right:

- Pick a supplier that is a good fit for your needs

- Avoid any unfavorable terms, for example, pre-payment in full before production (as crazy as it sounds, it still happens)

- Have an idea of where the final assembly is taking place, and also where the critical components come from if possible

- Document your quality standard, teach your supplier about it, and confirm that they reach the same conclusions as your own quality team when checking the same samples

- Make sure the products you buy are safe and comply with the importing countries’ regulations

- Get the supplier to sign an enforceable manufacturing agreement, among others (a lawyer can help advise what is needed, and hopefully you have a budget for that).

If the factory is starting to make a new product for you…

Are they developing a new product, or starting to put it in production? This calls for a certain approach that is different from mass production. I wrote about the NPI process for electro-mechanical products before, and here are some important tips:

- Do at least 2 meetings per week, at a fixed day & time, all the way from product development until at least the end of the first mass production. Keep a list of issues (weighed by their importance) and go over it every time.

- Get someone to complete a process flow chart when they start to go into a pre-production pilot run and get them to indicate what the key areas to improve are. If they can’t/won’t plan ahead, a company like ours can go on-site, observe, and suggest what areas to work on. (We suggested a checklist in this article.)

- Start to document a process FMEA and a process control plan if possible. (Read this article if you are not sure what it is about.) These are living documents, they should be updated at least once a week until at least the end of the first mass production. The FMEA should become a to-do list (addressing each one of the highest-ranked failure modes).

- Someone at the factory should also be using those documents to do a weekly audit of the manufacturing & testing processes. Someone external could do 1 or 2 of those audits, too. There are always remarks that point to improvements.

- And, of course, product inspections during & after production are important. Catching issues earlier will save time for both parties and will save a lot of cost to the manufacturer.

If the product is mature and already in mass production…

Here are, again, a few pieces of advice that will help detect some big issues:

- Conduct at the very least a final random inspection on every batch. If there are good reasons to be worried, better also conduct a first-article inspection (toward the start of assembly) and/or an inspection during production when about 20% of the quantity is completed.

- Also do ongoing reliability testing — this is especially useful on electronic products, to detect if there has been a big change in a component, for example, because of an effort at cheating the product or simply because a supplier messed up.

- Corrective action requests + annual re-audit on the quality management system, to keep the pressure to improve and work more systematically.

- Regular visits from someone from your company. There is no substitute for that. At least twice a year, I’d say.

Now, what about their recurring issues? How to get rid of them?

A lot of companies scold their suppliers and punish them with chargebacks. Like an adult would do with a kid, typically.

If you are ready to show the supplier some respect, and if the supplier is ready to open up a bit about their operations, there is a very different approach, which is sometimes called Weak Point Management.

If you have been suffering recurring defects, and/or if you are aware of some manufacturing/testing processes that need to be the focus of serious improvement work, that’s the right approach. If you want to go in the direction of zero defect, you have to use that approach at one point.

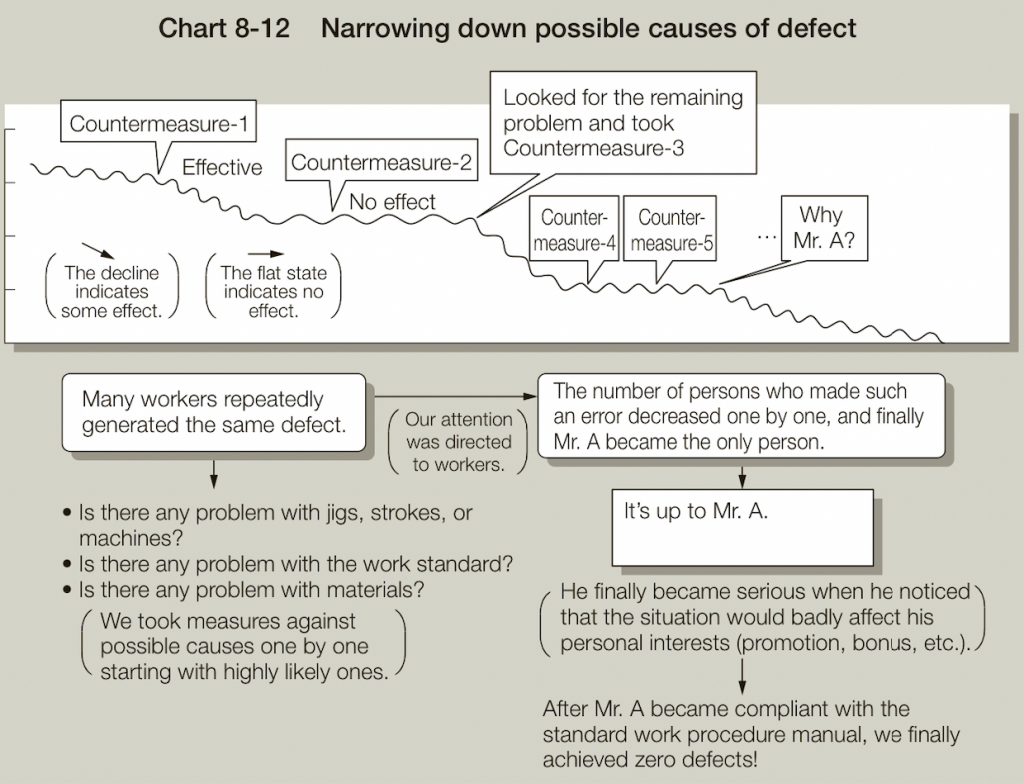

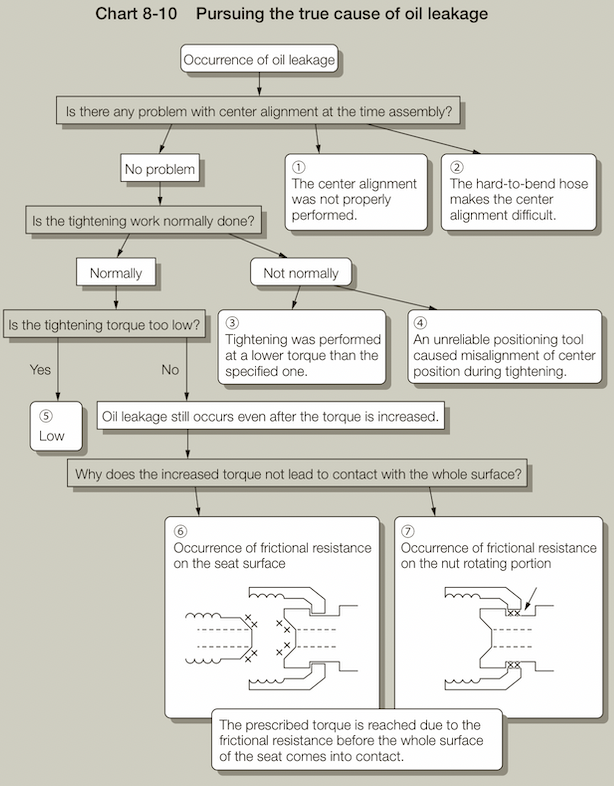

It starts with visualisation. So, to show a couple of examples, I pulled some graphs from the book The Toyota Way of Dantotsu Radical Quality Improvement.

Here is an example that leads to a typical and frustrating finding: a certain employee doesn’t apply the level of care needed, and the local supervisors have to deal with “Mr. A”.

Here is another example that deals only with technical topics.

Weak Point Management

I won’t pretend to cover Weak Point Management in one article, and I certainly won’t cover it as well as the book I mentioned above. In a few words, it requires an intense focus on the issues that lead to the highest number of defects. One issue at a time, in-depth, until the process is improved and has shown that the countermeasures are effective.