I listed the 6 ways Chinese suppliers cheat importers a few years ago. But, with proper due diligence, the risk of being cheated outright goes down a lot.

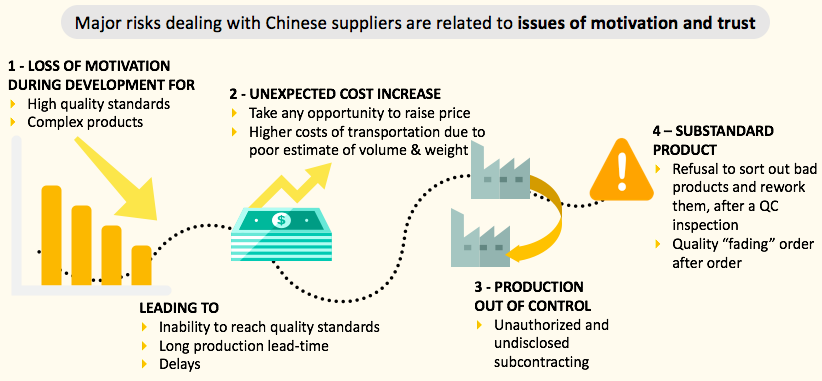

The major risks that experienced importers run, when working with a new manufacturer in China, are mostly related to issues of motivation and trust. To be sure, there are many good manufacturers in China, but you should be aware of the pitfalls and watch out for them.

My partner Fabien and I made a list of 7 common issues we have observed over the past few years.

1. Loss of motivation of the Chinese factory during new product development

In other words, the factory managers don’t believe in the business potential. They are not motivated and don’t provide sufficient resources. They don’t say it outright, but they have many excuses for delays.

Frequency: medium to high. We see it at least 30% of the time when a new product is being developed with a Chinese manufacturer. They think one or two iterations will be sufficient, but it takes more time and effort before production can be launched. The only thing they want to focus on is production.

Example — The feet of a speaker was made of various plastic and aluminum parts. The customer sold the speakers in a high-end distribution channel and had high-quality standards. Multiple iterations were necessary. After a while, the supplier started not answering emails, phone calls, and Wechat messages. Progress became more and more difficult over time, delaying the entire project by 6 months.

2. Inability of production to reach the required quality standard

Once the supplier fully understands the implications of the customer’s quality standard, they refuse to produce at that standard and invoke high production costs.

Frequency: medium to high. It happens about 50% of the time when buyers have to make high-end products (think Apple products, paper bags for Chanel, and so on). The supplier’s production process cannot reach the standard consistently, and they have to sort out a large proportion of bad products.

Example — multiple defects (dots, scratches, areas without plating…) appeared on a plated brass part. The electroplating supplier (a sub-sub supplier from the importer’s standpoint) had very poor process controls, resulting in 80% of defective parts. One solution was sorting the plated parts after processing, but the 20% yield meant the production output was way below target. It caused serious delays, increased production costs, and made it necessary to add multiple inspection checkpoints in three factories (metal material, plating, and final assembly).

3. Low priority in the production schedule

The factory is used to much larger orders, or the product to build is technically more complex than what they usually make. Either the lead time is very long, or there are many last-minute delays that keep adding up.

Frequency: high for long lead time (about 80% of the time), medium for delays (30-50% of the time).

Example — some highly customized metal drinkware were made by a Zhejiang factory. They had experience and were an approved Walmart supplier. They were making large batches or relatively simple products, with a focus on low cost. They showed a complete lack of interest in the small and complex order of drinkware. They kept mentioning ‘production is on schedule’ until the inspection day when not a single piece was finished! It took 3 extra months, as well as stationing one person full time on site, to get to the point where the batch could be shipped out. And yet, the buyer had a solid contract and didn’t skip any step in the development process (they had even done a pilot run).

4. Production costs are out of control, with the supplier taking any opportunity to raise the price

The supplier takes advantage of customer changes, or even their own mistakes, to say “by the way, we have to raise the price”. The higher price gets way above the buyer’s target.

Frequency: low to medium — maybe 30% of the time. Particularly likely if the supplier doesn’t expect a long-term business relationship with the buyer.

Example 1 — a metal assembly plant in Guangdong province added unreasonable labor cost (their calculations included operator salaries up to 6 times higher than the minimum wage) and material costs (much higher than market prices) for any change, be it prior to or during production. The manufacturer was hiding all the sub-suppliers. When they made a mistake, they also asked for payment in full, with the justification that the customer’s request was not clear enough and they had to meet the deadline. The product price had increased by more than 20% by the time of the first shipment.

Example 2 — after the development of a smart suitcase was finished (including electronics and software), the manufacturer doubled the price (+100%). The buyer’s margin totally disappeared. As could be expected, the manufacturer ensured the software and hardware could not be copied (no way to know the source code or the chip). This situation led to a double failure, for the manufacturer (no order) and for the buyer (who had invested in the product development).

5. Unauthorized and undisclosed subcontracting

The buyer is led to believe that production will take place in one factory, which is often audited and formally authorized. Then, when the time comes, production is placed somewhere else — very often in a young factory that has immature systems, very little support staff, and offers a low price.

Frequency: medium (about 30-40%). The more the buyer has a presence in China and the more closely the buying team follows things, the less likely it is to happen.

Example 1 — a Hong Kong trading company gave an order to a garment factory in Foshan. The end buyer (a European company) flew a technician to China to supervise the start of production — making sure the sewing machines were correctly set up, etc. The factory forced the trading company to increase the price due to the product’s complexity (see point 4 above). And, unbeknownst to all, they subcontracted production to a small workshop. Quality was terrible.

Example 2 — a Taiwan-owned manufacturer was given an order of wooden boxes. The buyer was quite impressed after the factory visit and sent them a 100% pre-payment (in effect, setting an incentive to the supplier to do a bad job). A small workshop makes the boxes. Quality was terrible. The factory refused to do anything — they adopted a “take it or leave it” attitude.

6. A refusal to sort out bad products and rework them, after a QC inspection

An inspector finds serious quality issues. The customer is unhappy and asks them to fix the problem. The supplier takes a little time, says the batch is now acceptable, and a new inspection shows the same problems.

Frequency: relatively high (50-60%) if the customer does not take things in hand. Even higher if the supplier knows that the importer MUST deliver products soon — after all, the shipment will be authorized in the end, so why do the work?

Example — a batch of underwear was refused due to a high number of workmanship defects. The Chinese trading company said they would do the rework, but the factory did nothing. The re-inspection, the re-re-inspection, and the re-re-re-inspection showed no changes. The customer was charging every re-inspection to the trading company, which in fact had no control over the factory. Even the team of inspectors said they didn’t want to go back there — it was useless and frustrating for everybody.

7. Logistical cost increase due to poor estimate (from the supplier) of volume and weight

For some importers, a higher cost of transportation can mean no margin. And many Chinese suppliers are not very careful when estimating the volume and weight of a batch of packed products.

Not only does it affect cost, but it also delays shipping if the total volume doesn’t fit in the container that has been booked (or in the allocated space in the plane).

Frequency: very high. In 90% of cases, the volume and/or the weight are poorly estimated.

Example — a batch of silicone goodies was supposed to be 20 cubic meters (cbm). It was supposed to fit easily in a 20 feet container. When loading the container, they noticed that the volume reached 30 cbm… and could not fit (the limit in real capacity is around 28-29 cbm). In the end, the container could not be loaded, the boat shipment was missed, and a new 40” container was booked for the following week. There was a one-week delay and a 30% increase in transportation costs.

—

Have you noticed other issues that come up again and again?

Are you trying to find a manufacturer in China who is well-suited to your needs and can also deliver on their promises?

Sofeast has developed 10 verification steps to help importers find the right manufacturing partner in China. They’re shared in this FREE eBook: “How To Find A Manufacturer In China: 10 Verification Steps.”

It covers:

- Background checks

- Manufacturing capabilities

- Quality system auditing

- Engineering resources

- Pricing, negotiation, & contracts

- …and much, much more

Just hit the button below to get your copy and put yourself in a great position to get better results from Chinese manufacturers who supply your products:

Great list, sadly I’ve experienced all of them one time or another! Add….

#8…. Downhill quality drift on repeat orders….

Despite written agreements and repeated communications about keeping production process stable, many factories will make small tweaks on future orders to reduce costs. At first these may be very subtle — e.g. shifting the process target. Say, length spec is 10.0 +/- 0.5 mm. First batch averages 10.0, “dead nuts” on target, great Cpk. Second batch is 9.7 average, all in spec but low. Third batch is 9.5 average with 20% of pieces below spec. If nothing is caught, fourth batch may well be 9.4 average with 80% out of spec… and so on. Factory has just reduced raw material costs by 6% — great for the bottom line, not so good for quality. And if you don’t stop them they’ll keep going!

This kind of tweak is especially dangerous if the characteristic requires complex testing, say, something like plating thickness or weld penetration. They know you can’t easily and cheaply check it.

I had one factory do this repeatedly with welds. They got shorter and shorter. At first they blamed the workers who were paid piecework on manual welds, rushing the work. I stopped shipment several times and required additional welds. Their proposed corrective action was to automate the welding… good idea, I said. They did automate; the new welds were great on the first order… then somehow the next order the weld fillet size got smaller. Turned out that the operator of the welding machine increased the weld speed to get more production. Next CAR: putting the weld controls under lock and key. We’ll see in my next visit how someone figures out a way around the locks… I am confident that the production people have the ingenuity to find a gimmick!

One countermeasure to this: as Sofeast and other experts recommend, keep a “gold standard” master sample from the first batch approved on hand. Use this as the reference standard. Second countermeasure: on site process audits, doing your own random sampling and SPC.

That’s absolutely true! Many people call it ‘quality fade’ and agree that the 3rd or 4th shipment are the most dangerous… if the 1st one was acceptable.

Interesting examples, thanks Brad!

Renaud,

Another spot on list and Brad beat me to the punch adding the Quality Fade issue. Some of the effects of the listed issues can be reduced by correctly written contracts (and written in Chinese), but the costs of these issues need to be allowed within project costing.

Peter

Thanks Peter. Yes a lot can be done to prevent these issues, but realistically some of them are going to appear at one point.