Many of our clients design their own products. And we typically don’t get involved in the initial concept/ideation phase. That’s clearly not our competence, nor our offer.

However, we are often invited to ask questions about their new product idea, to test if their concept is manufacturable, to confirm it won’t be extremely hard to develop, etc.

And we see the same patterns, over and over. Many people don’t talk a lot to potential users/customers when planning for the features. They don’t document the typical conditions of use. And so on.

And one of these patterns is, people tend to pick a solution and go full steam ahead. Even if there are serious unknowns.

We usually suggest a feasibility study and/or making a ‘proof of concept’ prototype. And people often push back (after all, we are delaying the development of the new product).

Slowing down and confirming the unknowns in the new project does not come naturally. I just read a good book from Matthew May entitled Winning the Brain Game: Fixing the 7 Fatal Flaws of Thinking that suggests how to fight this tendency.

One key concept is what May calls “prototesting“. In other words, making several crude prototypes, mostly for the sake of testing them and learning enough to get closer to a good solution.

At the beginning, build and test, don’t overthink

Kindergarten kids are good at building innovative solutions because they do many small experiments, each one refining the previous ones. They are better than business school graduates, who tend to apply planning and project management tools.

Here is an example of such an experiment.

What is the reason for this poor performance of business students and managers?

- A ‘project management’ type of approach aims at implementing a certain solution reliably.

- Kindergarten kids don’t worry about reliability in reaching an outcome. They are busy aiming at finding a valid outcome in itself. And that should be the first step when designing a new product… yet it is often overlooked.

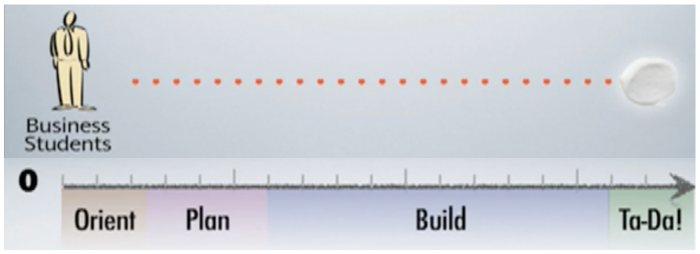

I grabbed some nice graphs from the video above. Business students try to follow a series of sequential steps and only consider one approach:

In contrast, kindergarten kids try something, see how how it works, try something else, and so on. By the time they get to the end of the 20 minutes, they tend to have a better solution:

The key is to go through many cycles of trying and learning. Each cycle includes these 4 steps: hypothesis, prototype, test, reflect.

How to set a good hypothesis that can be tested and (hopefully) confirmed?

Matthew May suggests the following process:

- Make a list of “what must be true” statements.

- Look for those that might not be true. They are to be tested in priority.

- Express them as “We believe [action/capability] will likely result in [desired outcome], with [metric] [significantly changed].”

- Then, you are ready to prototype and test those risky assumptions in the simplest way possible (often a very crude proof-of-concept prototype) to generate learning.

For example, let’s say you need a device that will be used to clean horses. It will have to be close to their ears, so the noise cannot be high. A “must be true” statement is “the device can fulfil its function under 56 dB”.

The time then comes to plan and execute a ‘proof of concept’ prototype: “We believe a thick plastic enclosure, together with motor XYZ, will likely result in a quieter device that will not frighten horses, with the noise level under 56 dB.”

At this stage, engineers need to look for a (hopefully) quick & simple way of putting parts together and testing the result. Whether it fails or it succeeds, the experiment led to a learning point.

Testing several directions before deciding on the one best approach

People who imagine how their new product will work tend to decide very early on the best way to proceed. And that may well be a mistake.

As Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon wrote in The Sciences of the Artificial:

It is often efficient to divide one’s eggs among a number of baskets – that is, not to follow out one line until it succeeds completely or fails definitely, but to begin to explore several tentative paths, continuing to pursue a few that look most promising at a given moment.

It depends on the size of the undertaking, naturally. If you just want to have a good dinner, make a pick and go to one restaurant. If you are planning spend years developing a new product, and investing a good chunk of your savings into that project, spend some time in the initial planning phase!

*****

What do you think about this ‘prototesting?’ Have you followed a similar path to test new product ‘unknowns’ during your NPD process? Let me know by commenting, please.

Are you designing, or developing a new product that will be manufactured in China?

Sofeast has created An Importer’s Guide to New Product Manufacturing in China for entrepreneurs, hardware startups, and SMEs which gives you advance warning about the 3 most common pitfalls that can catch you out, and the best practices that the ‘large companies’ follow that YOU can adopt for a successful project.

It includes:

- The 3 deadly mistakes that will hurt your ability to manufacture a new product in China effectively

- Assessing if you’re China-ready

- How to define an informed strategy and a realistic plan

- How to structure your supply chain on a solid foundation

- How to set the right expectations from the start

- How to get the design and engineering right

Just hit the button below to get your copy (please note, this will direct you to my company Sofeast.com):