China, as a whole, has 35+ years of experience manufacturing products for export customers. They have accumulated a lot of experience.

However, foreign buyers are rather consistently shocked at the level of mismanagement that plagues their factories’ quality operations. And fixing it is not that hard.

In this article, I will lay out what I see as the 4 basic roles that manufacturers need to fill in their quality department.

Typical issues with quality management in factories

If you have spent time working closely with Chinese manufacturers, as I have, you have probably noticed these issues (and others):

- Poor understanding of each customer’s needs and requirements (and, more fundamentally, very poor new product introduction process)

- A lot of inspections, sorting, and rework (but not very effective because of the above point)

- The quality manager is often the best person at covering up the issues and avoiding some of the blame from customers

- No systematic effort at stabilizing operations by fixing recurring problems, both internally and with key suppliers

- No prioritization of projects based on importance and based on what the data say. Since operations are not stabilized, there are emergencies every day and the focus is on them.

This situation does not get better if the factory’s general manager does not make the effort to understand the nature of the problems.

What I have seen, in many cases, is a quality manager being hired from outside with the mandate to “keep customers happy and give them confidence”… and reproducing the same typical approach that doesn’t work well.

Let’s look at what is actually needed

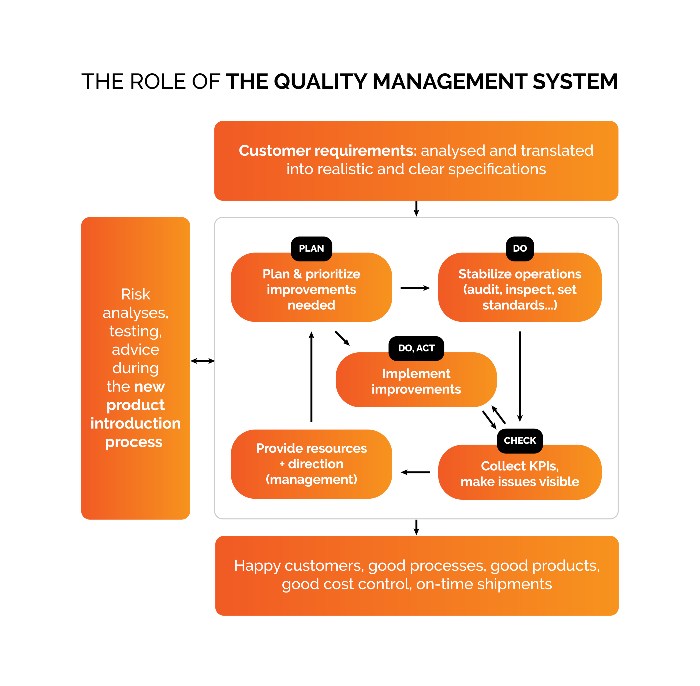

Now, let’s look at the basic functions a factory’s quality department is supposed to perform:

- Understand customer requirements, translate them into specifications

- Support the new product introduction process, if new products are developed

- Plan for improvements needed in the systems & processes, prioritize them and provide resources (competences etc.) as needed

- Stabilize operations by setting standards; checking, checking, checking in order to detect problems early; providing quick feedback to the source of the issues

- Work on the improvements planned previously

- Collect key performance indicators in order to show if improvements were effective and to find where to direct more attention; make issues visible so they are tackled and their recurrence is prevented

I summed all this up in this graph:

Now, when it comes to HR management, there are basically 4 employee profiles needed. Let’s cover them one by one.

#1. Checkers: people who check, check, check, in a consistent manner and are dedicated to their mission

They could be inspectors, or (if they have good analysis and people skills) auditors. They have good attention to details and they don’t mind doing repetitive work. They tend not to be very eager to help other people, which means they cannot be influenced easily – they have a standard, they work to it, and they point to discrepancies, period.

If a factory likes to hire them with 5 or 10 years of experience, and good written English, they are expensive. If they are hired after 1 year working for another factory, and if they have enough basics about English to improve on it and get to the right level after 1 year, they are much cheaper, and they usually wouldn’t mind doing other low-level work when needed. This approach brings a lot of benefits but it takes some planning and some management & training.

In the same logic, some production operators have a good eye for issues and can be trusted to do this work. It could be a promotion patch for some junior operators. Cross-training brings many benefits. Maybe people might object “but they still see the production supervisor as their boss”, and that’s true, but is it a problem if they work under the supervision of someone dedicated to the quality department who will be present and can avoid any type of “negotiation”?

Working 6 days a week is a must for this type of work. However, long hours are dangerous if they do a lot of visual checks. Keeping them at work after 8 hours is OK if there is a big job one day, but is not advised if it happens every day.

Those people could be sent to suppliers’ factories if they are known to behave well and are not easily influenced. No need to pay someone a Supplier Quality Engineer’s salary if they just do inspections of parts in a supplier’s factory… or even if they just audit a process.

In the long run, in a well-managed manufacturing plant, production becomes more and more responsible for quality. The quality department is still needed for risk analyses and reviews at pre-defined points, for providing clear standards, for helping with failure analyses and the management of corrective actions, and with specialized knowledge about testing. And the quality department should keep auditing what the production department does but should do much less product inspection.

#2. The specs person: someone who understand customers (and typical end-users) well, and can translate those needs into technical specs

This is a key position that is very often missing. Someone with some empathy and past experience in a wide range of products can be very helpful. A previous experience in a testing lab or an inspection company could be a plus. Good English is generally needed.

They should be able to build a checklist, to pick boundary samples, etc. and to make the link between OQC standard and IQC standards. An SQE (Supplier Quality Engineer) is usually more focused on the supplier side than the customer side and is probably not a good fit for this position. However, an SQE (or an experienced inspector) can review IQC standards.

This person is typically very involved in the NPI process, as support to the salespeople (and to the project managers). It may have to be a foreigner with a technical background.

#3. Improvers: people who see system and process issues and can drive improvement

This profile is analytical but also has good people skills (particularly in persuasion and empathy).

Ideally, that person is able to:

- Understand situations and see what the major issues are, and prioritize them in a smart way (based on how serious the issue is, on the ease of improvement, on the need for resources, etc.)

- Develop a plan that makes sense, and explain it

- Get the buy-in from people who will have to help in implementing the plan

- Have the persistence to carry the plan out

If that person is not very good at step 1, that’s not a disaster. Management can tell him/her what the priorities are. But he/she has to be good at steps 2, 3, and 4.

The work can be internal (in the factory’s own operations) or external (in the component suppliers’ operations). Sometimes there is a lot of work internally, sometimes externally, so small manufacturers will want to keep employees flexible when it comes to their scope of work.

It is much better if that person already has experience in implementing a quality management system and knows how flexible that system can be… and keeps it simple and well suited to the needs of the company.

A good process engineer is often a good person to do this work. I believe it is usually better to avoid someone with a quality background. A good process engineer already knows the basics of quality and can be trained where needed.

I would even say, that role is not necessarily in the quality department. He could be under the production manager in a relatively small factory if it makes improvement easier. Someone under the production manager could still work on pushing a supplier to improve, for example, since that has an impact on production performance.

A 5-day workweek is usually fine. Maybe that person can be requested to do a bit of work on his/her laptop at home on Saturday to do an update on the plans etc.

Someone “very good” in this position may save the company 5 or 10 times more money than someone “just good”.

#4. And finally… the manager of the quality department

The main roles of the quality manager are:

- Ensure the right balance between improvement and stability. Using the “improver” to drive positive changes, but making sure standards are updated in a smart way so that checkers/auditors can help keep those standards in place.

- Work with HR management to plan for the right skills and develop them over time.

- Visual management. KPIs, standards and work instructions, deviations from the standard, improvement plans, progress (or lack thereof) on the plans, etc. should be as visual as possible. Communication is important. Everyone needs to have an understanding of these topics.

- Ensure quick feedback to the sources of problems, and ensure there is a known process for dealing with those problems.

- Ensure the quality team cooperates well with other departments. Quality is, in good part, a support function. But it also has to enforce standards, so it’s a mix of soft and hard, depending on the situation. Each employee’s role and responsibility has to be very, very clear.

- Coach the quality team so they do their work well, they get used to filling 8Ds the right way, they fully understand their role in the company, etc.

- Reassure customers (there is a quality manager, hopefully speaking English, with a lot of experience, etc.)

There is a risk to avoid, though. If the quality manager is the same person as the ‘improver’, the urgent work of his manager position will take precedence over the importance of improvement work, and no improvement will happen. (Urgent always wins over important.)

It would be great if the quality manager has done some ‘improver’ work in the past and can guide the person doing the ‘improvement’ work, but I believe they should usually be 2 distinct people in the long run.

As operations get bigger and more complex, more people need to be hired to handle the urgent issues, and who will allow the quality manager to keep focusing on the important work. Those are usually quality engineers and/or assistant quality managers.

Benefits of staffing these 4 roles as I advised above

A factory that follows my advice can be expected to:

- Keep the salaries of most employees (the checkers) relatively low.

- Have great specifications and a good understand of what their customers need and want, which prevents complaints.

- Have someone dedicated to driving long-term improvement, without having to jump on every daily interruption.

- Have a strong system in place relatively fast. Note: I wrote before about setting up a “minimum viable quality system” in a new manufacturing company, based on our experiences structuring our subsidiary Agilian.

- Have a lot of ways to reassure customers and show a competitive advantage (and really, in many industries in China, a well-run quality department is a major competitive advantage.

Sofeast: Quality Assurance In China Or Vietnam For Beginners [eBook]

This free eBook shows importers who are new to outsourcing production to China or Vietnam the five key foundations of a proven Quality Assurance strategy, and also shows you some common traps that importers fall into and how to avoid or overcome them in order to get the best possible production results.

Ready to get your copy? Hit the button below: