Let’s explore the different sampling pans that you may come across when conducting QC inspections…

Editor’s note: This post has been updated in Jan 2026.

1. What is a sampling plan?

A sampling plan allows an auditor or a researcher to study a group (e.g. a batch of products, a segment of the population) by observing only a part of that group, and to reach conclusions with a pre-defined level of certainty.

In this article I cover these cases in-depth (hit the links below to skip to the relevant section):

- The buyer wants to follow the most common plan to inspect a supplier’s batch of products

- The manufacturer implements a continuous sampling plan, as products come out of the production process

- An ‘acceptance on zero’ plan is implemented

You can also watch this post as a video slideshow:

If you’d like to download the slides and keep them for future reference, please get them here.

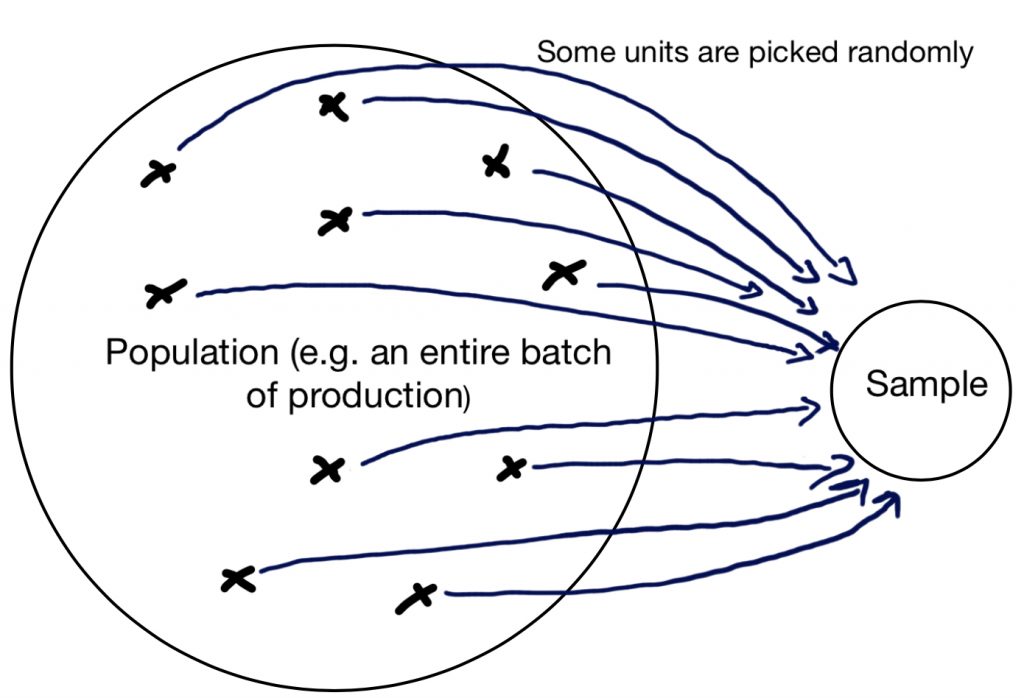

What is random sampling?

In most cases, units from the group (or ‘population’) are picked at random.

In a random sample, all units/parts have the same likelihood of being selected for inspection.

Is it always necessary to inspect/test a sample in order to draw a conclusion about an entire batch?

No, it is not. If you check 50 watches costing 200 USD each, it might make more sense to check all 50 of them, one by one.

In contrast, if you purchase 4 containers of Christmas balls costing 24 cents each, it makes no economic sense to check 100% of them! You need to work on the basis of random sampling.

2. Statistical sampling plans

If an inspector controls the quality of your products in China, he probably checks only a portion of the whole batch.

But how does he decide how many pieces to pick for his inspection? How does he decide what number of defective units is “too many”? And how certain is he to make the right decision, since it is based on his findings on a random sample?

Let’s say you decided to draw samples from a batch of products.

An unsophisticated approach to sampling often looks like this:

Take 10% randomly, and check these pieces.

- How can you make the link between this plan and your risk as the buyer (of accepting a batch that is worse than what you are willing to accept)?

- Let’s say you find 3% of the samples you picked are defective. You are left negotiating with the factory, with no previously-agreed rule to decide if they should take action (e.g. sort out the whole batch and set aside the issues).

****

To make this topic more lively and accessible, I made some “whiteboard-style” videos that you will find in section 3 (below).

But first, what is your situation?

3. Situation 1: You buy a batch of products and you want to use the most common sampling plan

The most popular plan was developed by the US Department of Defense, and was formalized in standards MIL-STD 105E, 2859-1, and ANSI Z1.4. Many people call it an “AQL inspection”.

I described it in this in-depth article about the AQL. And I made a rather in-depth video about the way it works, its risk implications, and its limitations:

If you purchase some products from overseas suppliers, they will probably refer to this approach. And, if they are not familiar with any other type of sampling plan, you should probably stick with it.

4. Situation 2: You are a manufacturing organization and you want to follow good practices

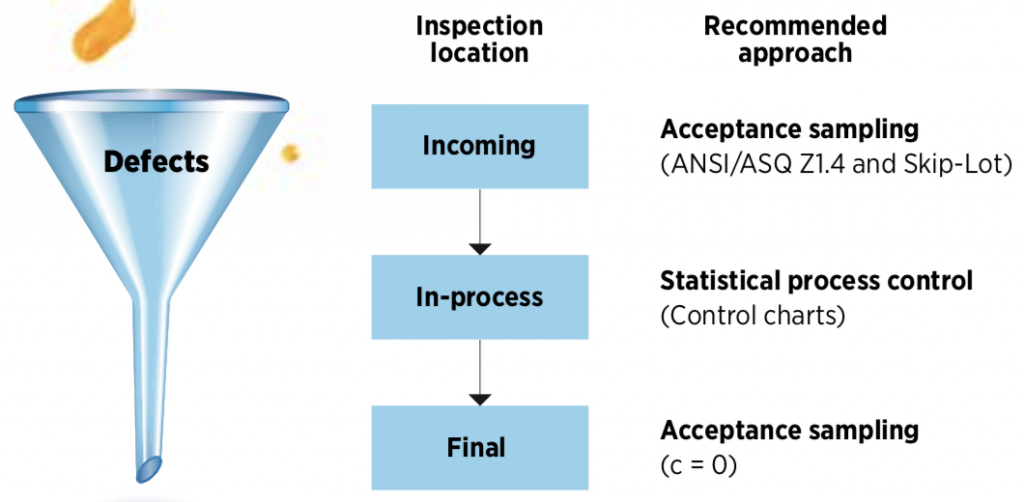

Manuel E. Peña-Rodríguez wrote an article about this in Quality Progress April 2018. He makes a distinction between three stages:

Manuel E. Peña-Rodríguez wrote an article about this in Quality Progress April 2018. He makes a distinction between three stages:

a) Incoming inspection — you need a cost-effective way of checking a number of batches. An “AQL inspection” works well (see section 3 above).

b) In-process control — the approach here is usually a combination of:

- Process controls (e.g. a C or P control chart) — this is outside the scope of this article.

- Product controls (e.g. a continuous sampling plan) — we cover it below, in section 4.2.

c) Final inspection — you still want a filter here, in order to stop batches that still have defects. The right approach depends on your situation:

- If you are in general consumer goods, setting AQL limits a bit tighter than what your customer would select is often a “good enough” solution (see section 3 above).

- If you can’t afford to ship even a few defective goods, an acceptance on zero plan makes more sense (see section 4.3).

Now let’s look at each type of plan outlined above, one by one.

4.1 Incoming QC: Acceptance sampling plan based on MIL-STD 105E, ISO 2859-1, ANSI Z1.4

If you purchase batches of products from an external company, and those batches are made in a continuous or semi-continuous manner with no changes in process or components, it does make sense.

If you are curious about the way the statistics behind this plan work, you can watch this video:

Statisticians have given us many variations on this plan. Let’s look at two of these.

a) How many times are samples picked?

- I am guessing that, in more than 90% of cases, a “single stage” approach is followed. It means a certain number (n) of pieces (n) are drawn and inspected. That number n depends on the size of the batch and on the inspection level. If the number of defects is under the AQL limit, the result is passed.

- A “double-stage sampling plan” is a bit more efficient. The inspector would start by taking a smaller number of sample (n1). If the finding is not clear (not very good, not very bad), more samples are picked.

- There are also multiple and sequential plans. They are more complex and require more administrative follow-up, but they are even more efficient.

b) Is every batch checked?

- Again, I am guessing that in over 90% of cases the buyer decides to check every single batch. When a batch is not checked, this decision is not derived from statistical rules.

- A skip-lot plan, in contrast, allows the buyer to inspect only a fraction of the batches, based on past performance. The way to decide when it can apply, and what the fraction should be, is similar to that which I’ll describe in section 4.2.

4.2 Continuous sampling plan (MIL-STD-1235B)

This approach makes sense when these conditions are met:

- Inspection is quick and results are known very fast

- No destructive test is involved

- Product quality is known to be relatively stable

- Products are identical (same materials going through the same process under the same specifications) — they can be made in a continuous flow or in batches

I made a video to explain how it works:

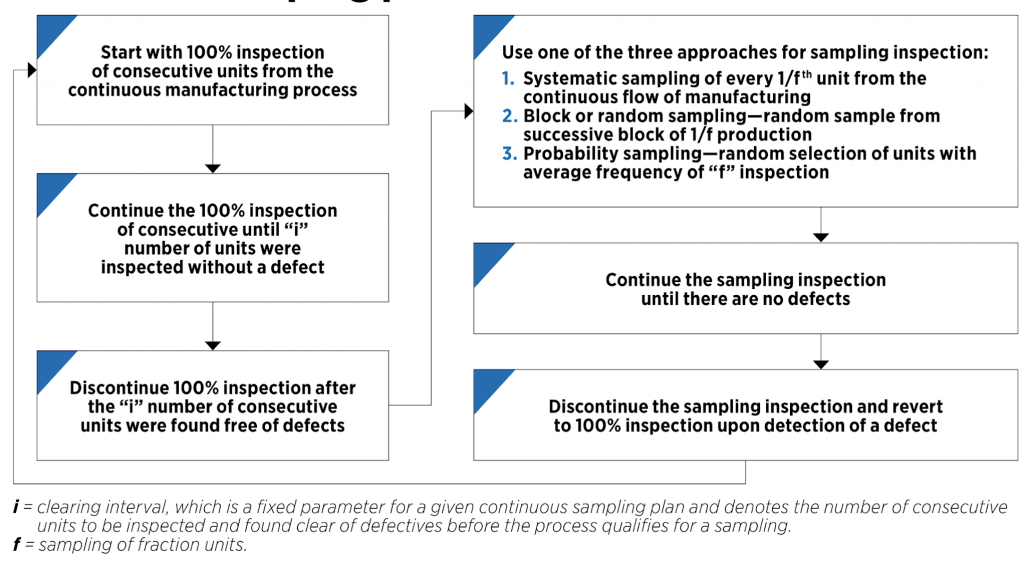

It consists of several phases:

- In the beginning, each piece is checked (that’s “100% check” or “screening”).

- After a certain number of pieces were found satisfactory, only certain pieces are checked randomly (that’s the “sampling”).

- If a piece is defective: back to screening.

- If screening lasts for a long time (meaning defective units are often found), the priority is to improve the process and/or to set up testing at the source to catch issues immediately.

It is summarized in this flowchart:

(Source: Quality Progress)

Here again, statisticians have given us many different flavors. I only covered the most common type of continuous plan (CSP-1). It might not fit your situation (for example, too many samples to check), and the MIL-STD 1235B standard might offer something more suitable.

5. Situation 3: You want to implement an ‘Acceptance on zero’ sampling plan

Some importers, who are sensitive to legal litigation by their customers or who have high-quality standards, accept batches only if no defective unit is found. This is common in industries such as automotive or pharmaceutical.

In some cases, the producer itself adopts this type of approach for its outgoing quality control. One big advantage is the fewer samples need to be checked. In principle, it only makes sense if the process has a capability index (Cp) of at least 1.67. (In simple terms, the key characteristics of the product are measured and they fall within the specifications in the vast majority of cases.)

Here also, I shot a video where I explain this based on an example.

What are the differences between the traditional acceptance plan (ISO 2859-1 / ANSI Z1.4)?

- There are no inspection levels.

- Rejection is always as soon as 1 defective unit is found.

6. A few other types of sampling plans

I can’t cover all types of sampling plans used for quality control purposes. But here are three others.

- I only covered plans “by attributes”, which classify the samples as either “non-defective” or “defective”. If a plan is “by variables”, it allows for a finer evaluation. For example, the length of the product is measured, and the exact findings are taken into account when a decision is made.

- A “rectifying” is applicable if the defects that are found can be corrected immediately. It takes into account the fact that the batch is of higher quality after the inspection… and, in case of inspection failure, the whole batch should be inspected.

7. Helpful resources

You can visit the excellent SQC Online website and get many of the numbers you will need.

And if you want more in-depth information about these plans, you should read Practical Acceptance Sampling: A Hands-On Guide.

If you like to base your approach on an ISO standard, the first step should be to read The Different Sampling Plans Contained in the ISO 2859 Series.

What do you think?

FAQs

Q: What is a sampling plan?

A: A structured method to inspect a subset of a lot and decide accept/reject with defined risk.

Q: Single vs double vs multiple sampling?

A: Single uses one sample; double adds a second sample if borderline; multiple uses staged sampling to reduce average sample size.

Q: When should I avoid AQL plans?

A: For unique/low‑volume lots, safety‑critical goods, or when ongoing series switching rules don’t apply.

Q: Can I combine SKUs into one lot?

A: Risky, non‑homogeneous lots distort representativeness and decision risk.

Need help with inspecting your production?

Get in touch with me, and I will give you a tailored recommendation or quotation. My company Sofeast, can probably help you.

Sofeast: Quality Assurance In China Or Vietnam For Beginners [eBook]

This free eBook shows importers who are new to outsourcing production to China or Vietnam the five key foundations of a proven Quality Assurance strategy, and also shows you some common traps that importers fall into and how to avoid or overcome them in order to get the best possible production results.

Ready to get your copy? Hit the button below:

—

Editor’s note: This post was originally published in 2012, and has since been updated in Dec 2018 to include new information and formatting.

0 Responses

In the North American auto industry it is common to use an acceptance number of zero nonconformities, on the basis that:

1) Process capability studies have been done in advance and prove that when the process is kept in control, the probability of nonconforming product is extremely small (e.g. parts per million.)

2) If a single nonconformity is found, the batch is segregated for a 100% rectifying

inspection.

These practices are generally incorporated into the production process, using a process similar to the “continuous sampling” plan discussed above. There will be a first piece approval for each process, where, say, the first 5 pieces of the shift will be checked. If any are out of specification, the process will be corrected and a new

first piece check done. If nonconformities are found after an hour of production, a

100% check back to the last :”in control” point will be done.

This protocol has been the expectation for many years (at least 30 in my recollection).

The justification here is that the finished automobile is the result of an assembly of thousands of individual parts. A single defective part can have serious consequences – for example, a single bad piston can result in poor performance of the engine. One client of mine makes bolts used for assembling engines; a few bad bolts (worth $.50 usd each) can result in the recall of the vehicle (cost of $2,000 – $5,000 per vehicle). So there is zero tolerance for defectives.

While no one will admit it for the record, the tolerance is greater for appearance issues – say, for example, paint quality. There is certainly an effort to control

appearance, but the subjective nature of appearance checks demands a little more latitude.

Brad

Very interesting, thanks a lot Brad!

As you point out, working on processes (in addition to doing manual inspections) is necessary to have the best results.

Renaud, do you have any other suggestions of books or online courses for people that want to learn more about QC inspection procedures and sampling?

I have learned from reading directly the ISO2859 standard, the book I mentioned above, and by talking to people in the industry. But I am sure there are other good sources of information.

can you tell me how many box to be opened for sampling of packaging material according to AQL (MIT STD 105,ISO 2859).

The standards you cite above say nothing about the number of cartons to pick. They only specify how many units of the product to pick.

In general, inspection agencies pick at least the square root of the total number of cartons (example: pick at least 10 boxes if there are 100 boxes).

Hi:

What if I needed to test variables AND attributes on the same sample unit ? (For example: length and some marks/labels in a watch)

Do you know any standard or sampling plan for that situation?

Can I use the sample for attributes for testing variables? (assuming non destructive tests)

Thank you

Wow. A sampling plan that takes both variable and attribute data into account? I never heard of that. I’d simply “transform” the variable data into attribute data…