This is the eighth part in the series about the management of QC inspectors in China.

This is the eighth part in the series about the management of QC inspectors in China.

Different companies give different job descriptions to their inspectors. I don’t think there are “best practices” here, but this is an important topic and I want to cover it.

The primary role of a QC inspector

Inspectors should collect and report information. They should not take decisions, in order to reduce the risks of bribery.

Similarly, they should not try to solve the problem with the factory. The goal here is to maintain a level of objectivity. It doesn’t mean they shouldn’t collect more information when they see a problem — for example doing a Pareto chart, observing what appears to be the point of cause, and gathering more data.

What I mean is, an inspector should let the factory work on determining the root cause(s) and testing countermeasures. She should not get involved in any decision. This way, when the time comes to check again, the inspector doesn’t feel she has to make a point. In addition, she usually doesn’t know the processes as well as the factory employees, so making a mistake is easy.

In a previous post (QA vs. QC), I defined quality assurance and quality control as follows:

QA = all the activities that aim at ensuring a certain level of quality. It includes defining what the requirement are + setting up a proper management system + QC.

QC = only the activities that consist of checking whether conformity is achieved or not. In the context of an importer who needs to secure his product quality, QC means checking if the specs are respected in production, and it translates into 2 types of activities: on-site inspections (statistical quality control) & laboratory testing (only on a few samples taken out of bulk production).

Some buying offices have a QA team and a QC team. The QA team tries to make everything go smooth. The QC team keeps the factories and the QA team honest and effective by checking their work. I think it makes a lot of sense.

What other roles for your field quality staff?

I like the way Samsonite (and others) have set up their quality teams:

- Quality control inspectors

- Quality auditors

- Quality engineers

Quality inspectors compare production to specifications. It is an entry-level job.

Quality auditors look at the quality systems. They point out any hole that might result in a quality problem not being noticed early enough. They also ensure the feedback loop is in place so that issues result in fixes at the source in a timely manner.

Quality engineers look at production processes and the way they are laid out. They look into serious issues and help the manufacturer implement effective and lasting corrective actions (and quality auditors will follow up and check if they are still in place in the future). They also try to suggest improvements that will impact quality and productivity. And they often work on new product developments with the manufacturers.

The challenge of process knowledge

Most QC inspectors can read and write English. They went further than secondary school — many of them have a bachelor degree. They were often hired as an inspector as their first job. In other words, they have never worked on a factory floor, either as an operator or as an engineer.

As a consequence, the best quality engineers are often hired after the first experience in a factory, and they seldom speak English.

The need for specific forms and training

In most cases, you should NOT count solely on your staff’s experience. They should follow a process.

Quality engineers are seldom given a formal process to follow.

What you want to avoid with your engineers is what Vince Leskowich calls the “shotgun approach to problem-solving“. Here is an example:

We have a plastic material cracking problem.

We changed the mold dimensions. Still cracked.

We changed the molding process parameters. Still cracked.

We changed the assembly method. Still cracked.

We annealed the parts after molding. Still cracked.

We changed the material. No cracks. It must be the material!

(But this old material has been used for the previous 5 years without a cracking problem. Nobody asks, “what changed? Why are cracks starting NOW after 5 years of running fine?”)

The reality is, the material was perfectly fine. It was just that it had not been dried correctly before use.

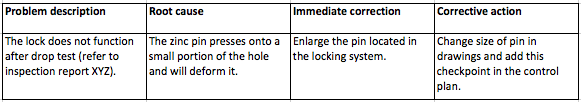

Instead, your engineers should approach problem-solving in a structured manner, as described in this article about troubleshooting. A very common form is the corrective action plan. Here is a simplified example:

The two areas where Chinese engineers tend to do a poor job (and need substantial training) are:

- Root cause analysis — they often remain at a superficial level.

- Followup — finding what to do is great, but will it really be done consistently?

—

What do you think?

Thanks Peter. I love the idea of having process engineers work on the lines for a few days.

And I can see why it would backfire in China. But, to be fair, it might work if their foreign managers did it too (working on the lines) for a few days… I have never seen that either. 🙂

Renaud, thats what I have done here myself,gone out and ran all our assembly equipment, molding machines, all variants, all our secondary machines, again all variants. This has allowed me to understand the processes and issues involved. By the way I mad my times on all but one machine after a few days. We later found that that machine had an impossible norm, and had it changed, and yes agreed it would be better if more Expat managers did get to the Gemba and do this. Peter

Renaud, once again on the money, also just because someone is a good QC does not mean they will be a good QA. I read with a slight smile the original Problem Solving Challenges post “thinking outside the box”, I personally prefer to see concrete evidence of thinking inside the box, before asking my engineers to think outside the box.

As an aside, another procedure we carried out in my former company with engineers (Process) quite successfully in the UK, Czech Republic and El Salvador was to have them work as operators in the line for a while to prove out our systems, and have them understand issues faced both by operators and engineers. This made them a more rounded engineer and we havested a host of improvements at the same time. We tried to implement a very simlar process here in China in 2002, and almost to a man the engineers quit. We were quite green in those days, and did not understand how this caused the loss of face to the engineers. Peter