I found myself warning a lot of companies recently about working with unsuitable manufacturers, and I thought I’d write about it. It usually unfolds this way:

- The buyer designs a new product and finds a manufacturer located in China that seems eager and offers low pricing.

- The Chinese manufacturer takes the design files, gets tooling made, and goes into production.

- The buyer is wise enough to insist on a small initial order.

- That first small order is disastrous at several levels — the buyer realizes the product design needs to change, and the manufacturer’s quality proves quite inconsistent and worrisome.

- The buyer needs to step back a bit and wonders what to do… often they keep working with the same manufacturer, and they end up regretting it deeply a few months later.

This is not an isolated incident. I found that just yesterday I spoke to 4 companies in this situation — two that haven’t decided yet to move away from the bad manufacturer, one that tried to make it work and is now facing the prospect of reworking thousands of products, and one that was wise enough to switch to a better supplier.

How to spot the warning signs of a manufacturer that cannot support your new product launch?

There are two ways this manifests.

a) The manufacturer doesn’t help you validate the product design

Here are typical red flags:

- They don’t run proper testing on the prototypes they prepare.

- They don’t review the design you have done on your side and suggest adjustments so it’s manufacturable (they want to push you to invest in tooling, but that means the tooling will probably need to be reworked).

- They don’t review the components you have picked on your side. For example, some components might be underrated and that can cause serious issues once the products are used.

- They don’t suggest reliability testing.

- They don’t even mention that they will need to make some extra prototypes to get the product certified/tested to comply with applicable requirements.

b) The manufacturer does not follow a systematic approach to design and validate the manufacturing process

Again, a few typical red flags:

- They don’t take the time to do a risk analysis.

- They don’t want to do a small pre-production pilot run. (Note: a good manufacturer would actually insist on doing it.)

- They don’t put the resources into setting up and documenting the quality standard, the checklist, test protocols, etc.

- They don’t develop test jigs and any other necessary tooling to confirm quality on production units.

- They can’t show you the work instructions needed to train & monitor assembly workers.

- You send a process auditor to look at their work, and he flags a number of serious issues.

What are the implications of working with such a manufacturer?

Picking a manufacturer that has no idea how to do the NPI process is often nothing short of catastrophic. Here are a few examples…

- An American company designed a product and then started to work with a factory that did not have much engineering or supply chain management capability. The first production run showed very serious production issues as well as product design issues that had not been addressed. The backlash from early users was such that the whole project had to be put on hold.

- An Australian company developed an innovative hardware product for their B2B customers. They went into production too early. The product design itself was not mature, and serious issues were found in manufacturing the first small batch. The supplier even claimed that the molds (which had been sold as hard-steel molds) had already reached their end of life after a few hundred shots. They spent months redesigning the product. They worked with the same supplier (and paid for the molds again) and went into relatively large production batches. The result was a very high rate of returns, as well as the painful and lengthy process of returning the products for rework in China.

- Let’s take yet another example. A British company switched to a supposedly better factory for their product’s second version. They let the manufacturer guide them. They went into a small production run that revealed serious issues both about the product design and the assembly & testing processes. They had to call us and it’s been a long (and expensive) project to rectify matters. The manufacturer had to devote resources to conduct a process FMEA and a control plan, and that work forced them to re-visit and re-engineer every aspect of the project.

I could keep going, but those examples are so similar I feel it becomes too repetitive.

The conclusion of all this is when you start to see those red flags, when you see that your manufacturer is ‘winging it’, just stop and look at your alternatives. The issues are probably deeper than you realize!

How does a project get into such a desperate situation?

The pattern is clear, and I will summarize it this way:

- There is a clear path for industrializing an electro-mechanical product, it is called the New Product Introduction (NPI) process.

- If both the buyer and the manufacturer have no prior experience with the NPI process, they don’t follow a structured approach, and they skip vital milestones.

- That leads them straight into a very painful situation where neither the product design nor the process design are ready for high-quantity, low-risk manufacturing.

I am sure many others have already described this painful situation. Elon Musk, who was forced to learn a lot about manufacturing over the past few years, talked about “production hell”. A suitable but much less catchy name would be “skipping NPI and going into manufacturing prematurely”…

How to switch to a better manufacturer?

That’s often difficult for a variety of reasons, including those:

- Tooling has been paid for, but there is often no contract that allows the buyer to push hard to pull it out.

- Some long lead-time components may have been purchased, already.

- There is a risk that the initial factory keeps producing an inferior product at a low cost and becomes a competitor.

Switching to a new, better manufacturer in cases like this is difficult but necessary. I can hardly remember any case where a manufacturer started very poorly and then got their act together and delivered great production runs.

Instead, the solution is usually to work with a better manufacturer that follows a structured process and has been working on products of the same complexity (but not necessarily in the same product lines) as yours. If you have already got the initial supplier to fabricate tooling for you, you need to look into your contract and see if you have the right to pull the tooling without extra costs. This might be necessary. If this is not possible, you might simply keep them as a supplier of the parts that are made from that tooling, assuming the geometry of those parts hasn’t changed.

In parallel, a good contract manufacturer might review the bill of materials and decide to change a good number of your component suppliers. That’s probable if you have been picking those suppliers without all the usual considerations to keep manufacturing risks low.

A better manufacturer is also likely to suggest some DFM improvements, take time documenting a quality standard, and so on. They need some time to do all the preparation work, and it’s painful because all that preparation should already have been done.

Maybe there is a way they make a few hundred products for you in a special way, all handled by engineers, at a much higher cost that is acceptable? Sometimes that’s the best alternative to calm down some vocal early customers/backers who can’t wait but can accept a product that is a bit short of your version 1.0.

Keep in mind, the inexperienced supplier has shown their limitations and, in the end, once you factor in all the time spent reworking, chasing issues, and so forth, and all the financial losses that it involves, that option is usually less desirable to your business.

If you really want to give your supplier a second chance, you can’t let them follow the same process that already led you into serious trouble. You need to take the project into your own hands and manage the DFM and industrialization of your product by yourself. Get ready to pay engineering bills yourself, just to compensate for the shortcomings of your supplier.

What does a good NPI process look like?

Let’s use our NPI process as an example here.

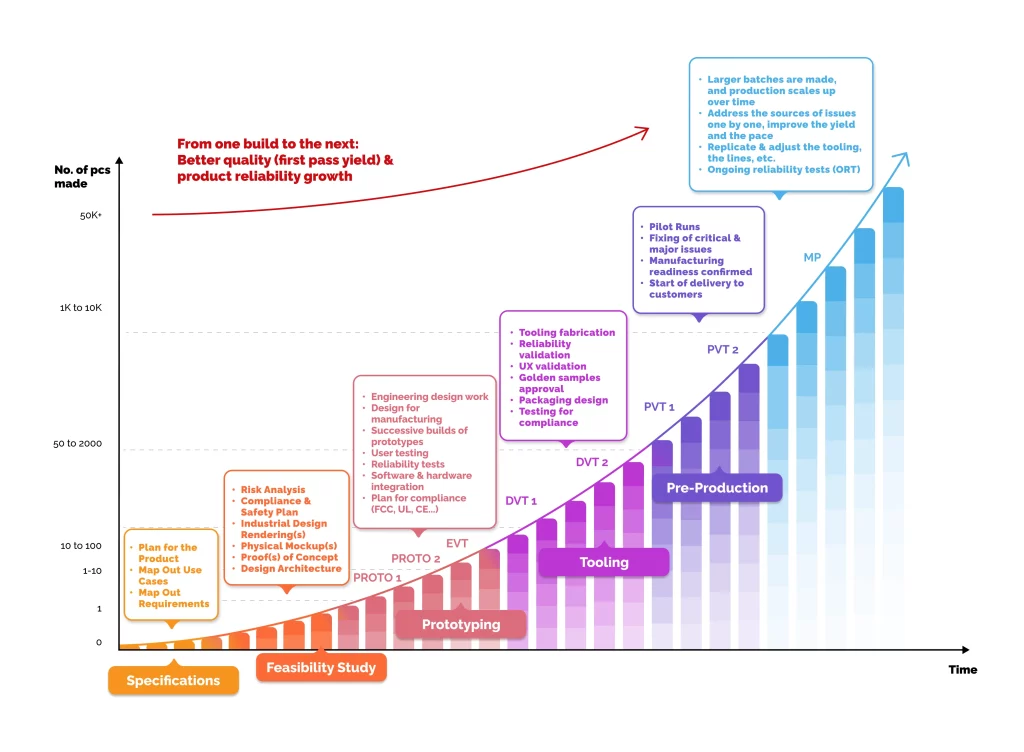

The point of the process is to have a structured set of phases to follow from product idea through to mass production that reduces the risks of things going wrong and finally results in your product being launched.

Each phase is a type of milestone that must have its constituent tasks completed in full before the project can move on to the next in order to keep risks low.

We created this graphic to demonstrate what the new product introduction process we follow looks like and the tasks included throughout (you can click the image to expand it):

I also talk through the 6 NPI phases here to explain each in more detail:

Finally, I mentioned that skipping the NPI phases (either through a wish to move fast or by mistake) is, usually, a mistake, and I explain why in this podcast: Why Skipping NPI Phases Is A Big Mistake [Podcast]