If you purchase goods from outside companies, and if you need to ensure that your products are of high quality, reliability, and safety, you need to focus on supplier quality management.

This takes different forms for different companies, of course. Let’s take two examples:

- Companies like Apple spend a lot of resources to qualify the right manufacturers, to ensure new products are developed with a low risk of issues, to monitor productions, etc.

- In contrast, a buyer of gift & premium giveaways will only do a quick check (such as “does the logo look good?” and hopefully also “does the product comply?”).

In spite of the vast differences between companies, and based on my 15+ years of experience on this topic, the general approach tends to be the same when managing regular, key suppliers that are seen somewhat as partners in the business.

1. Have you set supplier quality objectives?

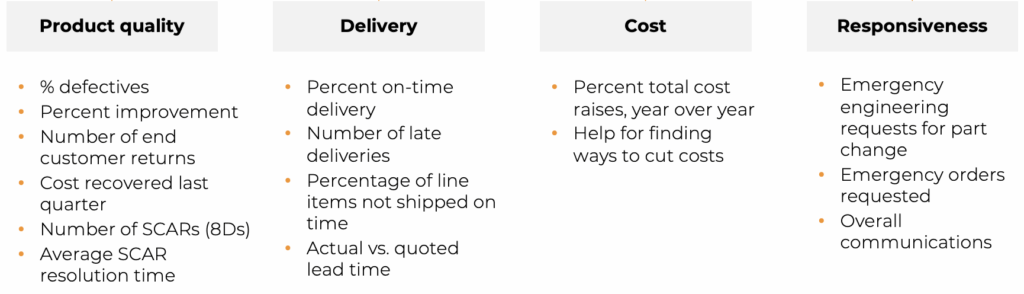

You probably pay attention to several dimensions of your suppliers’ performance. The most common are quality, on-time delivery, cost, and service/responsiveness.

Here are typical objectives.

Tracking the % defectives, the incidents where bad products were returned, the number of serious issues that lead to a supplier corrective action request (or 8D request — more about that later in this article), etc. is quite common.

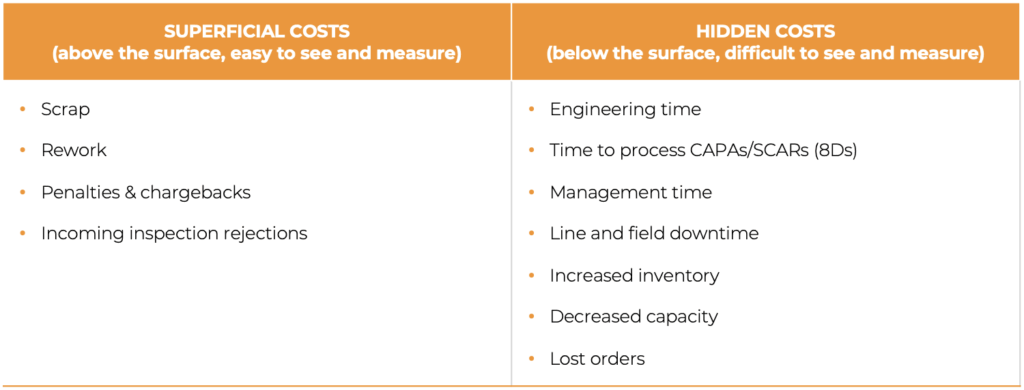

As a part of supplier quality management, it is also good practice to keep track of the costs of poor quality. Here are the most common sources of those costs:

Note: I shot a couple of videos about this — see How To Manage Chinese Suppliers based on Facts & Data.

2. It all starts when sourcing a new manufacturer

Many companies let their designers and/or buyers select new manufacturers, without input from their quality department. And that can lead to working with the wrong partners.

Here are five common ways to collect information in order to qualify or disqualify a company:

- Initial questions about the product – for example, “when will this display go ‘end of life’?”, “do we need this plastic to be food grade certified, to avoid paying for lab tests on every batch?”. Asking the right question now may save an enormous amount of work, costs, and time later on.

- Initial questions about the supplier – you need to make sure they are a good fit for you, and you are a good fit for them. It goes both ways. Make sure their capacity is sufficient, business seasonality won’t cause issues, they are motivated to work with you, and so on.

- Desk review of the supplier’s credentials – it can be a quick look at their admin records, or searching for any negative comments in Google, but it often involves requesting certain information and evaluating/verifying it.

- Factory audits – go on site and assess their quality system and/or their processes, in order to pinpoint the main risks of working with them. By the way, doing audits remotely may be necessary if travels are restricted, and it is better than not doing anything.

- Reliability testing on the supplier’s product – if you purchase a product already developed by the supplier, you want to have an idea of how durable (by applying high stress) and how reliable (by applying stress in a repeated manner) their product is.

Note: I recorded a series of podcast episodes about vetting Chinese suppliers that you may also find useful for learning more about the supplier sourcing and validation process.

3. Help the factory improve its quality system and their processes

When you work closely with a key supplier and have some weight over their decisions, you can push them to improve their operations.

I already wrote about some very commonly used tools to drive improvements:

- Process FMEA (risk analysis & mitigation)

- 11 Steps To Set Up a Process Control Plan

- Two Preventive Maintenance Examples

Now, if they do not want to make efforts to keep your business, or if they don’t want to work on improving their systems & processes, it will be difficult. That’s why, as I wrote above, it all starts with sourcing the right suppliers.

4. Are they developing a new product for you? Help them follow the right process

If a key supplier is developing a new product and if the stakes are high (e.g. high production volume coming up; high exposure to safety incidents…), you need to make sure they take it seriously and they follow the right process.

In simple terms, you want to ensure the new product doesn’t go straight from prototype to production. You want to make sure the product design, as well as the process design, are tested and validated. If you develop new products that are very similar to what the factory is already making, risks are low. If the product is going to be quite new, the risks of quality disasters are very high.

A very good and elaborate approach is the PPAP process in the auto industry. The supplier quality engineers (commonly called SQEs) ensure that a certain process is followed for every single part that will end up in a vehicle.

Depending on your industry, you might have to be very prescriptive (for medical devices under ISO 13485 + applicable regulations, or working under a PPAP), or you might have a lot more freedom.

You need to make sure the steps that are really needed are not skipped (think compliance and reliability tests, setting up a quality plan, pre-production pilot runs…), and at the same time, you don’t want to require so much work the project never crosses the finish line.

5. Monitor supplier quality performance

Here are two common ways to keep track of supplier quality performance:

1. Product inspections at the supplier’s factory – if some components or products are made in China and sent to you via an intercontinental shipping line, does it make sense to wait for those components or products and discover quality issues at that point? You probably can’t send products back for repair. You have certainly paid the goods in full. That’s not a good situation.

If a lot of money is at stake, you absolutely need to send an inspector to the factory, to detect any issues before shipment.

2. Incoming quality control in your facility – As you receive products, do you do at least a quick check, to confirm there is no problem?

Three years ago, I wrote an article about How to set up a Receiving Inspection: Checklist, Procedure, Reporting form, and I believe it is a solid guide you can follow if you need to set up incoming QC.

6. Feed the data back to the supplier

If your quality personnel only contacts your manufacturers when there is a complaint, they will only get those manufacturers to work in reactive, short-term mode.

If you spend some time once a month or once a quarter to compile the various data you have collected, and you feed that report back to each manufacturer, it is much more likely to drive long-term improvements.

Show that you follow the trends and that you have targets for them to reach. Focus on 1 or 2 key indicators if possible, to give them a very clear message.

Explain how it will impact the amount of business you will give them. When needed, show them that you are talking to direct competitors and that you might decide to reduce the business — that can be a powerful motivator.

7. Drive corrective actions for the most serious issues, so they don’t come back

When an issue has appeared, it is likely to come back again and again if the process is the same. That’s a sad truth. But it also means that, if the hard work of addressing those issues at the root gets done, those issues are not likely to come back.

Here is an example of the steps of a corrective action plan. (A pretty close approach to this is the 8D).

| Step | What to do? |

| 1. Clarify the Problem | What is the problem, how was it found and with what method, etc. Should more data be collected? |

| 2. Break Down the Problem | Analyze your findings. Is this due to only 1 problem? Or to several problems? Use a tree diagram and/or a Pareto chart if appropriate. |

| 3. Set a Target | What level of improvement do you (and the production staff) think is sufficient and realistic? |

| 4. Analyze the Root Cause(s) | Observe the process, the components, the products, etc. carefully. Ask the people who worked on the process for their opinion. What is/are the root cause(s) of the problem? Use a fishbone diagram if appropriate. Or use the flow chart that can be found here. |

| 5. Think of Corrective Action(s) | For each root cause, what should be done to avoid this problem in the future? Make sure to address causes at the root and to get the opinion of the production staff. |

| 6. Implement Corrective Action(s) | If the factory agrees, have them apply the corrective action(s). Otherwise, have them promise to do it later at a certain time. |

| 7. Monitor Results and Process | Are corrective action(s) well applied? Do they have an impact on processes? Are you finding an improvement? (Compare to target in step 3.) |

| 8. Standardize and Congratulate | If step 7 is positive, is the factory ensuring that the corrective action(s) will always be applied in the future? If they have done a good job, say thanks to the team who did it. |

I should mention two pieces of advice about corrective action plans:

- It does take training, so don’t just send a form for your supplier to fill if you are not sure they have a quality engineer/manager with experience in this exercise.

- It does take some managerial time, so you should make sure the manufacturer understands the gravity of the issue and the importance of preventing it in the future.

I wrote more on this topic in Use a Corrective Action Plan after a Failed Inspection, including some common traps.

8. Make it a system

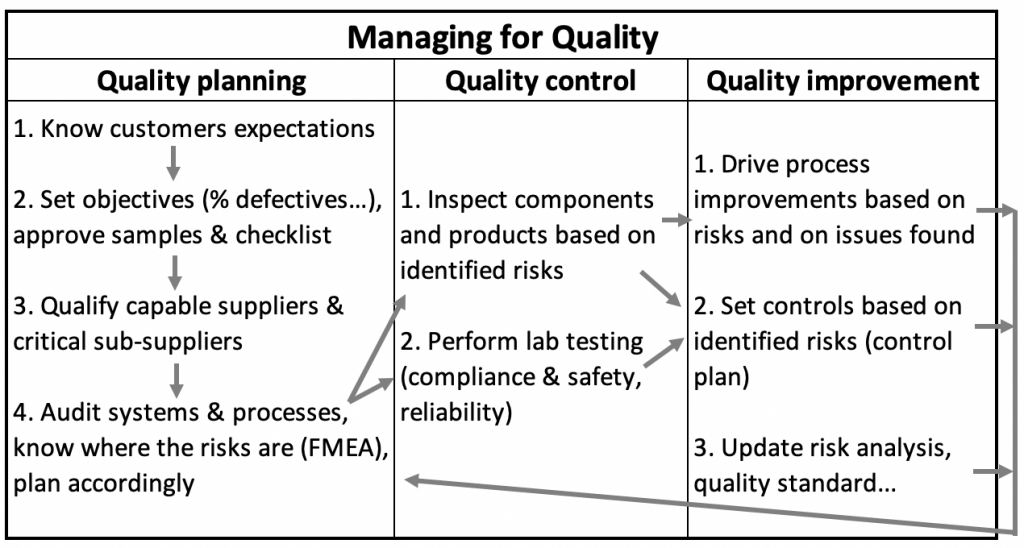

Everything I wrote above should be related, as part of a supplier quality management system.

I took the good old ‘Juran Trilogy’ and made a few changes to it. Here is a system that lives on a feedback loop.

Depending on your resources, you might do a complete loop every 3 months or every year, for every key supplier. That’s what supplier quality management entails.

Conclusion

To sum up, supplier quality management includes the whole supplier lifecycle, from initial qualification all the way to the end of the relationship. If you don’t keep putting resources into it and engaging factories, not only will quality probably not improve, but it may also drop!

The less mature a manufacturer’s quality management systems are, the more help they need from their customers. If you are serious about the quality of your product, make sure you recognize who needs more or less of that help.

Sofeast: Quality Assurance In China Or Vietnam For Beginners [eBook]

This free eBook, which is related to the topic of supplier quality management, shows importers who are new to outsourcing production to China or Vietnam the five key foundations of a proven Quality Assurance strategy, and also shows you some common traps that importers fall into and how to avoid or overcome them in order to get the best possible production results.

Ready to get your copy? Hit the button below: